NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012-.

LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet].

Show detailsOVERVIEW

Introduction

Rifapentine is a rifamycin antibiotic that is similar in structure and activity to rifampin and rifabutin and that is used in combination with other agents as therapy of tuberculosis, particularly in once or twice weekly regimens. Rifapentine is associated with transient and asymptomatic elevations in serum aminotransferase and is a likely cause of clinically apparent acute liver injury.

Background

Rifapentine (rif" a pen' teen) is a rifamycin antibiotic and a synthetic derivative of natural products of the bacterium, Amycolatopsis mediterranei. The rifamycins are complex macrocyclic antibiotics that have activity against several bacteria, but most prominently M. tuberculosis and several atypical mycobacterial species, probably as a result of inhibition of the DNA dependent RNA polymerase of mycobacteria. These agents are considered bactericidal and are active against both intracellular and extracellular organisms. Rifapentine has a longer half-life than rifampin and rifabutin, which allows for once or twice weekly dosing, which is its major advantage. Rifapentine was approved for use in treating active as well as latent tuberculosis in 1998. It is available as 150 mg film coated tablets under the trade names of Priftin. The recommended dose for active tuberculosis in adults is 600 mg twice weekly for 2 months, followed by 600 mg (~10 mg/kg) once weekly for 4 months as a part of directly observed therapy and in combination with isoniazid or other antituberculosis agents. The recommended regimen for latent tuberculsosis is a 12 week regimen of 600 mg once weekly in combination with isoniazid as directly observed therapy. Pyridoxine (vitamin B6) is commonly given with rifapentine and isoniazid to prevent neuropathy. Side effects of rifapentine are uncommon, but include rash, fever, flu-like symptoms, gastrointestinal upset and orange discoloration of urine and sweat. Rifapentine is intermediate between rifabutin and rifampin in activity as an inducer of the hepatic microsomal drug metabolizing P450 enzymes (CYP 1A2, 2C9, 2C19 and 3A4), the relative potencies being: rifampin (1.0), rifapentine (0.85) and rifabutin (0.4). For this reason, use of other medications (such as many antiretroviral agents, oral contraceptives, beta-blockers, benzodiazepines, cyclosporine, macrolide antibiotics and oral anticoagulants) with rifapentine should be carefully considered and monitored.

Hepatotoxicity

Because of its limited use, the effects of rifapentine on the liver have been less well defined than those of rifampin, but they are likely to be similar. Thus, long term therapy with rifapentine is associated with minor, transient elevations in serum aminotransferase levels in 2% to 7% of patients, abnormalities that usually do not require dose adjustment or discontinuation. Clinically apparent liver injury due to rifapentine has not been reported, but it is likely to be similar to rifampin in its potential for causing acute liver injury. Because rifapentine is usually given in combination with isoniazid and/or pyrazinamide, two other known hepatotoxic agents, the cause of the acute liver injury in patients on rifapentine containing regimens may be difficult to relate to a single agent, and some evidence suggests that these combinations are more likely to cause injury than the individual drugs. Typically, the onset of injury due to rifamycins is within 1 to 6 weeks and the serum enzyme pattern is usually hepatocellular at the onset of injury, but can cholestatic and mixed in contrast to isoniazid and pyrazinamide. Extrahepatic manifestations due to rifamycin hepatotoxicity such as fever, rash, arthralgias, edema and eosinophilia are uncommon as is autoantibody formation. This potential for hepatotoxicity has not been specifically demonstrated for rifapentine.

Likelihood score: E* (unproven but suspected cause of clinically apparent liver injury).

Mechanism of Injury

The mechanism of rifamycin associated hepatotoxicity is not known, but these agents are extensively metabolized by the liver and induce multiple hepatic enzymes. Thus, the cause of injury is likely to be due to idiosyncratic metabolic products that are either directly toxic or induce an immunologic reaction.

Outcome and Management

For rifampin, the severity of hepatic injury ranges from asymptomatic elevations in serum aminotransferase levels, jaundice without apparent hepatic injury, symptomatic self-limited hepatitis to severe fulminant liver failure and death. Complete recovery is expected after stopping the drug and is usually rapid and complete. The rifamycins have not been associated with vanishing bile duct syndrome or chronic hepatitis. There is likely to be some cross sensitivity to liver injury among the rifamycins (rifampin, rifabutin, rifapentine), but not with the other first and second line antituberculosis agents. Routine monitoring for seurm enzyme elevations is not recommended except in high risk individuals. Nevertheless, routine monitoring for symptoms of liver disease is recommended for all regimens, whether for clinically active or latent tuberculosis.

Specific, regularly updated recommendations on therapy of tuberculosis can be found on the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website: https://www.cdc.gov/tb/topic/treatment/

[First line medications used in the therapy of tuberculosis in the US include ethambutol, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, rifabutin, rifampin, and rifapentine. Second line medications include streptomycin, capreomycin, cycloserine, ethionamide, fluoroquinolones such as levofloxacin and moxifloxacin, aminoglycosides such as amikacin, and para-aminosalicylic acid (PAS).]

Drug Class: Antituberculosis Agents

Other Drugs in the Class: Bedaquiline, Capreomycin, Cycloserine, Ethambutol, Ethionamide, Isoniazid, Pyrazinamide, Rifabutin, Rifampin, Streptomycin

PRODUCT INFORMATION

REPRESENTATIVE TRADE NAMES

Rifapentine – Priftin®

DRUG CLASS

Antituberculosis Agents

Product labeling at DailyMed, National Library of Medicine, NIH

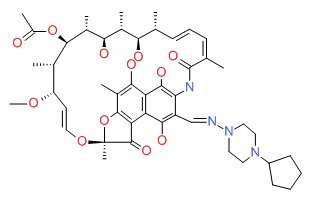

CHEMICAL FORMULA AND STRUCTURE

| DRUG | CAS REGISTRY NUMBER | MOLECULAR FORMULA | STRUCTURE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rifapentine | 61379-65-5 | C47-H64-N4-O12 |

|

ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY

References updated: 14 June 2018

- Zimmerman HJ. Antituberculosis agents. In, Zimmerman HJ. Hepatotoxicity: the adverse effects of drugs and other chemicals on the liver. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1999, pp. 611-21.(Extensive review of hepatotoxicity of antituberculosis medications including rifampin [but not rifabutin or rifapentine] published in 1999).

- Verma S, Kaplowitz N. Hepatotoxicity of antituberculosis drugs. In, Kaplowitz N, DeLeve LD, eds. Drug-induced liver disease. 3rd ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2013, pp. 483-504.(Review of hepatotoxicity of antituberculosis drugs).

- Gumba T. Chemotherapy of tuberculosis, mycobacterium avium complex disease and leprosy. In, Brunton LL, Chabner BA, Knollman BC, eds. Goodman & Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 12th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2011, pp. 1549-70.(Textbook of pharmacology and therapeutics).

- Acocella G, Lamarina F, Tenconi LT, Nicolis FB. Study of the excretion in bile and concentration in the gall bladder wall of rifamide. Gut 1966; 7: 380-6. [PMC free article: PMC1552415] [PubMed: 5917425](Rifamide had no effect on bilirubin levels, and high levels found in bile).

- Scheuer PJ, Summerfield JA, Lal S, Sherlock S. Rifampicin hepatitis. Lancet 1974; i: 421-5. [PubMed: 4131429](Analysis of 11 patients with hepatitis due to antituberculosis medications, some attributed to rifampin [none receiving it alone]; onset usually within 3 weeks, several having hepatitis with cholestasis).

- Allue X, Sanjurjo P, Fidalgo I, Bilbao F. Hepatic toxicity of antituberculous drugs in children. Helv Paediatr Acta 1976; 31: 381-7. [PubMed: 1017983](3 cases of jaundice in children, 2 boys and 1 girl, ages 8, 9 and 2 years, arising 14, 4 and 25 days after starting antituberculosis therapy with isoniazid and rifampin, two recovering upon withdrawal of rifampin only, one developed jaundice only when rifampin was added and subsequently died).

- Pessayre D, Bentata M, Degott C, Nouel O, Miguet JP, Rueff B, Benhamou JP. Isoniazid-rifampin fulminant hepatitis. A possible consequence of the enhancement of isoniazid hepatotoxicity by enzyme induction. Gastroenterology 1977; 72: 284-9. [PubMed: 830577](6 cases of fulminant hepatitis attributed to the combination of isoniazid and rifampin, 5 women and 1 man, ages 15 to 67 years, onset 6-10 days after starting INH and rifampin, all had encephalopathy [peak bilirubin 2.4-13.6 mg/dL, ALT 26-80 times ULN, protime 18-36%], without fever, rash, eosinophilia or autoantibodies, rapid onset, recovery in all).

- Taillan B, Chichmanian RM, Fuzibet JG, Vinti H, Taillan F, Dellamonica P, Dujardin P. [Jaundice caused by rifampicin: 3 cases] Rev Med Interne 1989; 10: 409-11. [PubMed: 2488482](3 women, ages 67 to 79 years, developed jaundice [2-8x ULN] within 6-7 days of starting rifampin with normal ALT, Alk P 2-3 times ULN, resolution in 14-30 days; in one biopsy showed “centrolobular cholestasis”).

- Chiu J, Nussbaum J, Bozzette S, Tilles JG, Young LS, Leedom J, Heseltine PN, et al. and California Collaborative Treatment Group. Treatment of disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex infection in AIDS with amikacin, ethambutol, rifampin, and ciprofloxacin. Ann Intern Med 1990; 113: 358-61. [PubMed: 2382918](17 patients with AIDs and MAC infection were treated with amikacin for 4 weeks and then 12 weeks of ciprofloxacin, ethambutol and rifampin; therapy stopped early in 2 patients for hepatitis, but no details given).

- Griffith DE, Brown BA, Girard WM, Wallace RJ Jr. Adverse events associated with high-dose rifabutin in macrolide-containing regimens for the treatment of Mycobacterium avium complex lung disease. Clin Infect Dis 1995; 21: 594-8. [PubMed: 8527549](Open label study of rifabutin in 24 patients with MAC; side effects were common and 3 [12%] had liver test abnormalities, one requiring dose modification who had a recurrence on reexposure).

- Schwander S, Rüsch-Gerdes S, Mateega A, Lutalo T, Tugume S, Kityo C, Rubaramira R, et al. A pilot study of antituberculosis combinations comparing rifabutin with rifampicin in the treatment of HIV-1 associated tuberculosis. A single-blind randomized evaluation in Ugandan patients with HIV-1 infection and pulmonary tuberculosis. Tuber Lung Dis 1995; 76: 210-8. [PubMed: 7548903](Controlled trial of rifabutin vs rifampicin in combination with isoniazid, ethambutol and pyrazinamide in 50 patients with HIV and tuberculosis; no clinically apparent liver injury or jaundice; rates of ALT elevations not given).

- Dautzenberg B, Olliaro P, Ruf B, Esposito R, Opravil M, Hoy JF, Rozenbaum W, et al. Rifabutin versus placebo in combination with three drugs in the treatment of nontuberculous mycobacterial infection in patients with AIDS. Clin Infect Dis 1996; 22: 705-8. [PubMed: 8729209](Rifabutin was used in 102 patients with MAC in European trials; no information on hepatotoxicity).

- Havlir DV, Dubé MP, Sattler FR, Forthal DN, Kemper CA, Dunne MW, Parenti DM, et al. Prophylaxis against disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex with weekly azithromycin, daily rifabutin, or both. California Collaborative Treatment Group. N Engl J Med 1996; 335: 392-8. [PubMed: 8676932](Controlled trial of azithromycin vs rifabutin vs both for prevention of MAC disease in 693 HIV infected patients; 1-2% of subjects developed laboratory abnormalities requiring discontinuation, a proportion being ALT elevations).

- Benator D, Bhattacharya M, Bozeman L, Burman W, Cantazaro A, Chaisson R, Gordin F, et al.; Tuberculosis Trials Consortium. Rifapentine and isoniazid once a week versus rifampicin and isoniazid twice a week for treatment of drug-susceptible pulmonary tuberculosis in HIV-negative patients: a randomised clinical trial. Lancet 2002 17; 360: 528-34. [PubMed: 12241657](Among 1004 patients treated with either rifapentine [once weekly] or rifampin [twice weekly] with isoniazid, ALT elevations >5 times ULN occurred in 2.6% on rifapentine and 3.5% on rifampin; no deaths due to liver injury).

- American Thoracic Society; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); Infectious Diseases Society of America. Treatment of tuberculosis. MMWR Recomm Rep 2003; 52 (RR-11): 1-77. [PubMed: 12836625](Detailed recommendations on therapy of tuberculosis including drug regimens [including rifabutin and rifapentine], side effects, monitoring and optimal approaches to follow-up).

- Reichman LB, Lardizabal A, Hayden CH. Considering the role of four months of rifampin in the treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004; 170: 832-5. [PubMed: 15297274](Review of the safety and efficacy of a 4 month course of rifampin monotherapy for treatment of latent tuberculosis).

- Marschall HU, Wagner M, Zollner G, Fickert P, Diczfalusy U, Gumhold J, Silbert D, et al. Complementary stimulation of hepatobiliary transport and detoxification systems by rifampicin and ursodeoxycholic acid in humans. Gastroenterology 2005; 129: 476-85. [PubMed: 16083704](Gene changes in liver after 1 week of rifampin, ursodiol or placebo in 30 patients undergoing electric cholecystectomy found increase in UGT1A1, CYP 3A4 and ABCC2 [MRP2], with significant decrease in serum bilirubin levels in patients receiving rifampin).

- Corpechot C, Ping C, Wendum D, Matsuda F, Barbu V, Poupon R. Identification of a novel 974C-->G nonsense mutation of the MRP2/ABCC2 gene in a patient with Dubin-Johnson syndrome and analysis of the effects of rifampicin and ursodeoxycholic acid on serum bilirubin and bile acids. Am J Gastroenterol 2006; 101: 2427-32. [PubMed: 16952291](Case report of patient becoming jaundiced on rifampin with no change in ALT or Alk P who had probable Dubin-Johnson syndrome, with mutation in ABCC2 [MRP2]).

- Munsiff SS, Kambili C, Ahuja SD. Rifapentine for the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 43: 1468-75. [PubMed: 17083024](Review of role of rifapentine, a cyclopentyl substituted semisynthetic rifamycin, similar activity and resistance pattern, but longer half-life allowing for once weekly therapy; efficacy may be slightly less than rifampin and it is recommended only in selected patients; side effects are similar to rifampin).

- Schechter M, Zajdenverg R, Falco G, Barnes GL, Faulhaber JC, Coberly JS, Moore RD, et al. Weekly rifapentine/isoniazid or daily rifampin/pyrazinamide for latent tuberculosis in household contacts. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006; 173: 922-6. [PMC free article: PMC2662911] [PubMed: 16474028](In trial comparing rifapentine with isoniazid for 3 months [n=206] vs rifampin and pyrazinamide for 2 months [n=193]; hepatotoxicity arose in 10% on pyrazinamide vs 1% on isoniazid combination, all resolved within two months, no hospitalizations or deaths).

- Saukkonen JJ, Cohn DL, Jasmer RM, Schenker S, Jereb JA, Nolan CM, Peloquin CA, et al.; ATS (American Thoracic Society) Hepatotoxicity of Antituberculosis Therapy Subcommittee. An official ATS statement: hepatotoxicity of antituberculosis therapy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006; 174: 935-52. [PubMed: 17021358](American Thoracic Society recommendations regarding hepatotoxicity of antituberculosis therapy; for latent infection, 9 months of isoniazid is first choice and 4 months of rifampin second; clinical monitoring is recommend for all patients and biochemical monitoring for those at high risk and possibly the elderly [ALT values at 1, 3 and 6 months or every 1-2 months]; hold therapy if ALT >5 times ULN or if symptoms are present and ALT >3 times ULN; mentions that hepatotoxicity due to rifabutin is uncommon and ALT elevations >3 times ULN were reported in 3-8% of patients receiving rifabutin for MAC prophylaxis; rifapentine is not discussed).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Trends in tuberculosis—United States, 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2009; 58 (10): 249-53. [PubMed: 19300406](In 2008, 12,898 cases of active tuberculosis were reported in US, lowest rate since reporting began in 1953; incidence rate=3/100,000; 1.2% with multidrug resistant strains).

- Gao XF, Li J, Yang ZW, Li YP. Rifapentine vs. rifampicin for the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis: a systematic review. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2009; 13: 810-9. [PubMed: 19555529](Systematic review of randomized controlled trials comparing rifapentine to rifampin in combination regimens for tuberculosis found no differences in rates of side effects including hepatotoxicity; no deaths or even hospitalization for liver disease reported in 3 trials involving 644 patients).

- Fountain FF, Tolley EA, Jacobs AR, Self TH. Rifampin hepatotoxicity associated with treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. Am J Med Sci 2009; 337: 317-20. [PubMed: 19295414](Among 205 patients treated for latent tuberculosis with rifampin [4 month regimen], 4 [2%] developed ALT or AST elevations above 5 times ULN [AST: 235-528 U/L] of whom 3 had elevations before therapy, only 1 was symptomatic; no mention of jaundice).

- Lobue P, Menzies D. Treatment of latent tuberculosis infection: An update. Respirology 2010; 15: 603-22. [PubMed: 20409026](Extensive review of the efficacy and safety of various regimens used in the treatment of latent tuberculosis).

- Leung CC, Rieder HL, Lange C, Yew WW. Treatment of latent infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis: update 2010. Eur Respir J 2011; 37: 690-711. [PubMed: 20693257](Review of the efficacy, adherence rates, cost effectiveness and safety of various regimens for the therapy of latent tuberculosis).

- Horne DJ, Spitters C, Narita M. Experience with rifabutin replacing rifampin in the treatment of tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2011; 15: 1485-9. [PMC free article: PMC3290133] [PubMed: 22008761](Among 30 patients with tuberculosis switched from rifampin to rifabutin because of liver test abnormalities, only two redeveloped liver injury on rifabutin, whereas 6 of 15 who were switched because of rash had a recurrence).

- Sterling TR, Villarino ME, Borisov AS, Shang N, Gordin F, Bliven-Sizemore E, Hackman J, et al; TB Trials Consortium PREVENT TB Study Team. Three months of rifapentine and isoniazid for latent tuberculosis infection. N Engl J Med 2011; 365: 2155-66. [PubMed: 22150035](7731 subjects with latent tuberculosis at high risk for active disease were treated with either a 3 month course of directly observed once weekly isoniazid and rifapentine [3 mo INH/R] or standard therapy with 9 months of daily isoniazid [9 mo INH]; after 3 years rates of active tuberculosis were similar [0.19% after 3 mo INH/R and 0.43% after 9 mo INH], whereas hepatotoxicity was less with 3 mo INH/R [0.4%] than 9 mo INH [2.7%]).

- Dorman SE, Goldberg S, Stout JE, Muzanyi G, Johnson JL, Weiner M, Bozeman L, et al; Tuberculosis Trials Consortium. Substitution of rifapentine for rifampin during intensive phase treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis: study 29 of the tuberculosis trials consortium. J Infect Dis 2012; 206: 1030-40. [PubMed: 22850121](Among 531 adults with active tuberculosis treated with isoniazid, pyrazinamide, ethambutol and either rifampin or rifapentine [5 days/week] for the first 8 weeks of intensive therapy, hepatitis was reported in 2.8% of rifampin and 4% of rifapentine treated subjects, the later group including 3 serious adverse events due to hepatitis).

- Björnsson ES, Bergmann OM, Björnsson HK, Kvaran RB, Olafsson S. Incidence, presentation and outcomes in patients with drug-induced liver injury in the general population of Iceland. Gastroenterology 2013; 144: 1419-25. [PubMed: 23419359](In a population based study of drug induced liver injury from Iceland, 96 cases were identified over a 2 year period, including 1 attributed to isoniazid but none to rifampin or other rifamycins).

- Hernández N, Bessone F, Sánchez A, di Pace M, Brahm J, Zapata R, A Chirino R, et al. Profile of idiosyncratic drug induced liver injury in Latin America. An analysis of published reports. Ann Hepatol 2014; 13: 231-9. [PubMed: 24552865](Systematic review of literature of drug induced liver injury in Latin American countries published from 1996 to 2012 identified 176 cases, 6 of which were attributed to isoniazid, 1 to pyrizamide and 1 to rifampin, but none to rifapentine).

- Stagg HR, Zenner D, Harris RJ, Muñoz L, Lipman MC, Abubakar I. Treatment of latent tuberculosis infection: a network meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2014; 161: 419-28. [PubMed: 25111745](Metaanalysis of 53 controlled trials of different regimens for latent tuberculosis concluded that rifamycin-only or isoniazid-rifamycin regimens had lower rates of hepatotoxicity than isoniazid-only regimens of 6, 9, or 12-72 months).

- de Castilla DL, Rakita RM, Spitters CE, Narita M, Jain R, Limaye AP. Short-course isoniazid plus rifapentine directly observed therapy for latent tuberculosis in solid-organ transplant candidates. Transplantation 2014; 97: 206-11. [PubMed: 24142036](Among 17 solid organ transplant candidates with latent tuberculosis who were treated with a 12 week course of weekly isoniazid and rifapentine, none developed ALT or AST elevations more than twice baseline or clinical hepatotoxicity during treatment and none developed active tuberculosis during follow up).

- Bliven-Sizemore EE, Sterling TR, Shang N, Benator D, Schwartzman K, Reves R, Drobeniuc J, Bock N, Villarino ME; TB Trials Consortium. Three months of weekly rifapentine plus isoniazid is less hepatotoxic than nine months of daily isoniazid for LTBI. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2015; 19: 1039-44, i-v. [PMC free article: PMC5080618] [PubMed: 26260821](Among 6862 patients with latent tuberculosis treated with either 9 months of daily oral isoniazid or 3 months of once weekly rifapentine and isoniazid, liver injury requiring discontinuation was more frequent with the 9 month regimen 1.9% vs 0.4%, as was symptomatic hepatotoxicity [1.3% vs 0.3%], but there were no hospitalizations or deaths from liver injury).

- Chalasani N, Bonkovsky HL, Fontana R, Lee W, Stolz A, Talwalkar J, Reddy KR, et al.; United States Drug Induced Liver Injury Network. Features and outcomes of 899 patients with drug-induced liver injury: the DILIN prospective study. Gastroenterology 2015; 148: 1340-52.e7. [PMC free article: PMC4446235] [PubMed: 25754159](Among 899 cases of drug induced liver injury enrolled in a US prospective study between 2004 and 2013, 408 were attributed to antimicrobial agents including 54 [6%] to antituberculosis agents, mostly due to isoniazid [n=48], occasionally pyrazinamide [n=2], rifampin [n=2] or ethambutol [n=1], but none to rifapentine).

- Knoll BM, Nog R, Wu Y, Dhand A. Three months of weekly rifapentine plus isoniazid for latent tuberculosis treatment in solid organ transplant candidates. Infection 2017; 45: 335-9. [PubMed: 28276008](Among 12 solid organ transplant candidates found to have latent tuberculosis infection who received 12 weeks of direclty observed therapy with weekly isoniazid and rifapentine, none developed de novo elevations of serum ALT more than twice baseline or had to discontinue therapy early because of adverse events, and none subsequently developed active tuberculosis).

- Simkins J, Abbo LM, Camargo JF, Rosa R, Morris MI. Twelve-week rifapentine plus isoniazid versus 9-month isoniazid for the treatment of latent tuberculosis in renal transplant candidates. Transplantation 2017; 101: 1468-72. [PubMed: 27548035](Among 153 renal transplant candidates with latent tuberculosis treated with 9 months of isoniazid daily or 12 weeks of weekly rifapentine and isoniazid, the 12 week regimen had a higher rate of compliance and lower rate of ALT and AST elevations [0% vs 5%]; subsequent activation of tuberculosis did not occur with either regimen).

- Chalasani N, Reddy KRK, Fontana RJ, Barnhart H, Gu J, Hayashi PH, Ahmad J, et al. Idiosyncratic drug induced liver injury in African-Americans is associated with greater morbidity and mortality compared to caucasians. Am J Gastroenterol 2017; 112: 1382-8. [PMC free article: PMC5667647] [PubMed: 28762375](Among 841 Caucasians and 144 African Americans with drug induced liver injury enrolled in a prospective US registry, the most frequent cause in whites was amoxicillin/clavulanate [13.4% vs 4.1%] and in blacks was trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole [7.6% vs 3.6%], whereas isoniazid represented 4% of cases in both racial groups).

- Zenner D, Beer N, Harris RJ, Lipman MC, Stagg HR, van der Werf MJ. Treatment of latent tuberculosis infection: an updated network meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2017; 167: 248-55. [PubMed: 28761946](A metaanalysis of 61 studies on regimens for therapy of "latent tuberculosis" found evidence of lower rates of hepatotoxicity with rifampin only or with short courses of isoniazid and rifampin in combination compared to longer isoniazid only regimens).

- PMCPubMed Central citations

- PubChem SubstanceRelated PubChem Substances

- PubMedLinks to PubMed

- Acquired rifamycin monoresistance in patients with HIV-related tuberculosis treated with once-weekly rifapentine and isoniazid. Tuberculosis Trials Consortium.[Lancet. 1999]Acquired rifamycin monoresistance in patients with HIV-related tuberculosis treated with once-weekly rifapentine and isoniazid. Tuberculosis Trials Consortium.Vernon A, Burman W, Benator D, Khan A, Bozeman L. Lancet. 1999 May 29; 353(9167):1843-7.

- Review Rifabutin.[LiverTox: Clinical and Researc...]Review Rifabutin.. LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury. 2012

- Potent twice-weekly rifapentine-containing regimens in murine tuberculosis.[Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006]Potent twice-weekly rifapentine-containing regimens in murine tuberculosis.Rosenthal IM, Williams K, Tyagi S, Peloquin CA, Vernon AA, Bishai WR, Grosset JH, Nuermberger EL. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006 Jul 1; 174(1):94-101. Epub 2006 Mar 30.

- Immunodeficiency and Intermittent Dosing Promote Acquired Rifamycin Monoresistance in Murine Tuberculosis.[Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2...]Immunodeficiency and Intermittent Dosing Promote Acquired Rifamycin Monoresistance in Murine Tuberculosis.Park SW, Tasneen R, Converse PJ, Nuermberger EL. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017 Nov; 61(11). Epub 2017 Oct 24.

- Review Rifamycins (rifampicin, rifabutin and rifapentine) compared to isoniazid for preventing tuberculosis in HIV-negative people at risk of active TB.[Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013]Review Rifamycins (rifampicin, rifabutin and rifapentine) compared to isoniazid for preventing tuberculosis in HIV-negative people at risk of active TB.Sharma SK, Sharma A, Kadhiravan T, Tharyan P. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Jul 5; 2013(7):CD007545. Epub 2013 Jul 5.

- Rifapentine - LiverToxRifapentine - LiverTox

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

See more...