NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012-.

LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet].

Show detailsOVERVIEW

Introduction

Chloramphenicol is a broad spectrum antibiotic introduced into clinical practice in 1948, but which was subsequently shown to cause serious and fatal aplastic anemia and is now used rarely and reserved for severe, life-threatening infections for which other antibiotics are not available. Chloramphenicol has also been linked to cases of acute, clinically apparent liver injury with jaundice, largely in association with aplastic anemia.

Background

Chloramphenicol (klor" am fen' i kol) is an antibiotic initially isolated from Streptomyces venezuelae and later characterized biochemically and synthesized. Chloramphenicol was introduced into clinical practice in 1948 under the brand name Chloromycetin and became a widely used antibiotic because of its oral availability, excellent tolerability and wide spectrum of activity. Chloramphenicol has bacteriostatic activity against many gram positive and gram negative organisms, both aerobic and anaerobic including H. influenza, N meningitides, S. pneumoniae, N gonorrhoeae, Brucella species and Bordetella pertussis. It also has activity against many spirochaetes, rickettsiae, chlamydiae and mycoplasmas. Chloramphenicol is thought to act by binding to the 50S ribosomal subunit in bacteria, thus inhibiting bacterial protein synthesis. A similar inhibition of protein synthesis may occur in mitochondria. Within a few years of its introduction, chloramphenicol was linked to rare cases of aplastic anemia and later to other fatal blood dyscrasias including thrombocytopenia, neutropenia and pure red cell aplasia. In addition, cases of leukemia were identified in children who had recovered from blood dyscrasias attributed to chloramphenicol. By the early 1960s, more than 1000 cases of severe bone marrow aplasia were attributed to use of chloramphenicol and it was widely banned or placed under restrictions, particularly in children. Currently, chloramphenicol is available only in parenteral forms, and its use is restricted to severe, life-threatening infections for which no other antibiotic is available because of antibiotic resistance or drug allergy. Several generic forms of chloramphenicol for intravenous administration are available and the recommended dose is 50 mg/kg daily in 4 divided doses. Monitoring for blood counts is recommended and prompt discontinuation for any evidence of myelosuppression.

Hepatotoxicity

A proportion of patients with blood dyscrasias due to chloramphenicol also developed clinically apparent liver injury with jaundice, usually occurring before the appearance of aplastic anemia or severe thrombocytopenia. Jaundice arises in 10% to 25% of cases of aplastic anemia, usually within 1 to 2 months of starting chloramphenicol and often shortly after it is stopped. Aplastic anemia and the accompanying liver injury occur most frequently in patients who receive multiple courses of chloramphenicol or prolonged therapy. The serum enzyme pattern is usually hepatocellular and the clinical presentation is an acute hepatitis-like syndrome with onset of fatigue, nausea, anorexia and abdominal discomfort followed by dark urine and jaundice. Rare instances have a cholestatic pattern of presentation with jaundice and itching and prominent elevations in alkaline phosphatase. Some cases occur in the absence of bone marrow involvement. Immunoallergic and autoimmune features are rarely present. The course is self-limited in most instances, but examples of acute liver failure have been reported, particularly in patients without aplastic anemia. In most cases, however, the liver injury associated with chloramphenicol use is eclipsed by the severe bone marrow aplasia.

Likelihood score: B (highly likely cause of clinically apparent liver injury, now rarely seen).

Mechanism of Injury

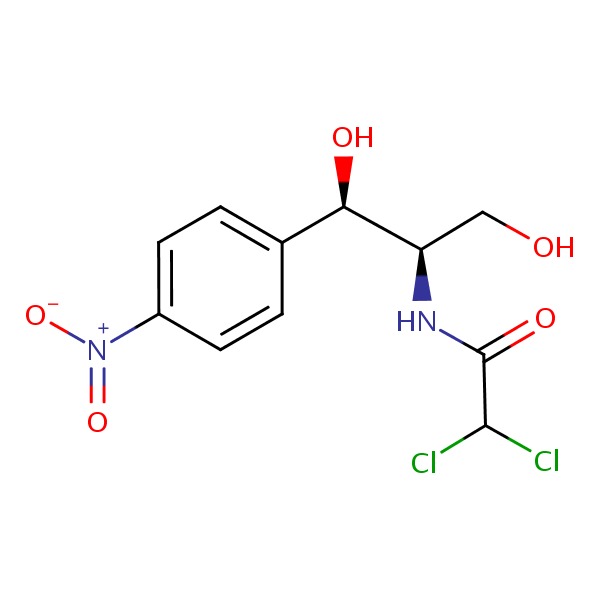

The etiology of liver injury associated with chloramphenicol is likely idiosyncratic and probably immunological. The hepatitis that accompanies chloramphenicol induced aplastic anemia is similar to the hepatitis that occurs with spontaneous or idiopathic aplastic anemia, suggesting a common pathogenesis of bone marrow and hepatic progenitor cell injury and loss. The marrow toxicity of chloramphenicol has been attributed to the nitrophenyl group in the molecule which is unique among microbial derived antibiotics.

Outcome and Management

The liver injury accompanying blood dyscrasias caused by chloramphenicol is often severe, but resolves rapidly in most cases only to be followed by signs and symptoms of bone marrow failure. Acute liver failure can result, but the role of liver transplantation in this situation is difficult because of the accompanying marrow damage and aplasia.

Drug Class: Antiinfective Agents, Miscellaneous

PRODUCT INFORMATION

REPRESENTATIVE TRADE NAMES

Chloramphenicol – Generic, Chloromycetin®

DRUG CLASS

Antiinfective Agents

Product labeling at DailyMed, National Library of Medicine, NIH

CHEMICAL FORMULA AND STRUCTURE

| DRUG | CAS REGISTRY NO | MOLECULAR FORMULA | STRUCTURE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chloramphenicol | 56-75-7 | C11-H12-Cl2-N2-O5 |

|

ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY

References updated: 24 January 2017

- Zimmerman HJ. Chloramphenicol. Hepatic injury from the treatment of infectious and parasitic diseases. In, Zimmerman HJ. Hepatotoxicity: the adverse effects of drugs and other chemicals on the liver. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1999. pp 589-92.(Expert review of hepatotoxicity published in 1999 mentions that the hepatic injury from chloramphenicol is eclipsed by its vastly more important myelotoxicity, but that at least 25 cases of liver injury with jaundice have been reported, usually with hepatocellular injury).

- Moseley RH. Antibacterial and Antifungal Agents. In, Kaplowitz N, DeLeve LD, eds. Drug-induced liver disease. 3rd Edition. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2013. p. 463-81.(Review of hepatotoxicity of antibiotics; chloramphenicol is not discussed).

- MacDougall C, Chambers HF. Chloramphenicol. Protein synthesis inhibitors and miscellaneous antibacterial agents. In, Brunton LL, Chabner BA, Knollman BC, eds. Goodman & Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 12th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2011, pp. 1526-9.(Textbook of pharmacology and therapeutics).

- Rich ML, Ritterhoff RJ, Hoffmann RJ. A fatal case of aplastic anemia following chloramphenicol (chloromycetin) therapy. Ann Intern Med 1950; 33: 1459-67. [PubMed: 14790529](63 year old man developed purpura 3 months after starting chloramphenicol, with subsequent aplastic anemia and death 2 weeks later; no mention of liver injury or jaundice).

- Volini IF, Greenspan I, Ehrlich L, Gonner JA, Felsenfeld O, Schwartz SO. Hemopoietic changes during administration of chloramphenicol (chloromycetin). J Am Med Assoc 1950; 142: 1333-35. [PubMed: 15412135](Three African-American males developed reversible granulocytopenia during chloramphenicol therapy despite beneficial response to the antibiotic).

- Winternitz C. Fatal aplastic anemia following chloramphenicol (chloromycetin) therapy. Calif Med 1952; 77: 335-9. [PMC free article: PMC1521482] [PubMed: 13009486](35 year old woman developed fatigue followed by jaundice one month after starting chloramphenicol [bilirubin 14.3 mg/dL, ALT and Alk P not available], with subsequent appearance of petechiae and aplastic anemia resulting in death within the next 3 weeks).

- Rheingold JJ, Spurling CL. Chloramphenicol and aplastic anemia. J Am Med Assoc 1952; 119 (14): 1301-4. [PubMed: 14938166](5 cases of fatal aplastic anemia developed in 4 women and one man, ages 18-36 years, who had taken chloramphenicol within the previous two months, none with hepatitis or jaundice).

- Sturgeon P. Fatal aplastic anemia in children following chloramphenicol (chloromycetin) therapy; report of four cases. J Am Med Assoc 1952; 149: 918-22. [PubMed: 14938069](4 children were admitted to a Los Angeles referral hospital over a 2 year period with aplastic anemia after chloramphenicol treatment, ages 2-6 years, 2-6 weeks after course of chloramphenicol resulting in fatal outcome, no mention of liver injury or jaundice).

- Claudon DB, Holbrook AA. Fatal aplastic anemia associated with chloramphenicol (chloromycetin) therapy; report of two cases. J Am Med Assoc 1952; 149: 912-4. [PubMed: 14938067](71 year old woman and 92 year old man developed aplastic anemia 2 and 6 weeks after multiple courses of chloramphenicol with fatal outcomes and aplasia of marrow; no mention of hepatitis or jaundice).

- Hargraves MM, Mills SD, Heck FJ. Aplastic anemia associated with administration of chloramphenicol. J Am Med Assoc 1952; 119: 1293-1300. [PubMed: 14938165](Description of 10 cases of aplastic anemia possibly attributable to use of chloramphenicol: latency 1-6 weeks, often with prolonged, intermittent or multiple courses, five in children, 7 fatal, one with jaundice preceding onset of petechiae and subsequent aplastic anemia).

- Hargraves MM. Aplastic anemia associated with the administration of chloramphenicol. Proc Staff Meet Mayo Clin 1952; 27: 280-1. [PubMed: 14941875](Further information on 6 cases of aplastic anemia attributed to chloramphenicol [Hargraves 1952], most of which were fatal, precipitous in onset and not responsive to corticosteroid or vitamin B12 administration).

- Smiley RK, Cartwright GE, Wintrobe MM. Fatal aplastic anemia following chloramphenicol (chloromycetin) administration. J Am Med Assoc 1952; 149: 914-8. [PubMed: 14938068](3 cases of fatal aplastic anemia in one 29 year old man and two young girls [6 and 8 years old] arising within a few weeks of exposure to chloramphenicol [all with prolonged or intermittent courses], without jaundice or liver injury).

- Hawkins LA, Lederer H. Fatal aplastic anaemia after chloramphenicol treatment. Br Med J 1952; 2 (4781): 423-6. [PMC free article: PMC2021158] [PubMed: 14944846](Two girls, ages 4 and 7, developed jaundice 39 and 49 days after starting 27- and 44-day courses of chloramphenicol for whooping cough [liver tests not provided] which lasted for a few days and was followed by bruising and progressive, ultimately fatal aplastic anemia).

- Wolman B. Fatal aplastic anaemia after chloramphenicol. Br Med J 1952; 2 (4781): 426-7. [PMC free article: PMC2021160] [PubMed: 14944847](6 year old developed fatigue and jaundice followed by bruising one month after finishing a 24 day course of chloramphenicol [bilirubin, ALT and Alk P not given], with subsequent aplastic anemia and death within a month; at autopsy the liver was enlarged and showed fatty change).

- Salm R. Acute necrosis of the liver following chloramphenicol therapy. Edinb Med J 1953; 60: 334-6. [PMC free article: PMC5290421] [PubMed: 13060295]

- Hodgkinson R. Blood dyscrasias associated with chloramphenicol. An investigation into the cases in the British Isles. Lancet 1954; 266 (6806): 285-7. [PubMed: 13131842](Mailed survey identified 31 cases of blood dyscrasias arising after administration of chloramphenicol in the UK, 28 aplastic anemia, 3 granulocytopenia, 8 [26%] preceded by jaundice, in all ages, 11 children, 13 male and 18 female, 24 fatal).

- Abbott VC, Marra JJ, Gell JW. Acute yellow atrophy of the liver following chloramphenicol (chloromycetin) therapy. J Mich State Med Soc 1955; 54: 474-6. [PubMed: 14368249](53 year old woman developed jaundice and rapidly fatal acute liver failure after a second prolonged course [~2 months] of oral chloramphenicol [bilirubin and liver tests not given], without evidence of aplastic anemia).

- Cable JV, Reid JD. Jaundice and aplastic anaemia following chloramphenicol therapy. N Z Med J 1957; 56: 532-5. [PubMed: 13483950](14 year old girl developed jaundice shortly after a 30 day course of chloramphenicol for acne [bilirubin 60 mg/dL, ALT not available, Alk P normal], which resolved over the next month, followed by easy bruising and evidence of aplastic anemia which led to death one month later).

- Brunton L, Shapiro L. Chloramphenicol and aplastic anemia: report of four cases. Can Med Assoc J 1962; 86: 863-5. [PMC free article: PMC1849189] [PubMed: 13874077](Four cases of aplastic anemia developing in 3 men and one woman, ages 40-81 years, presenting with bleeding, having received chloramphenicol within the previous two months, 3 fatal, no mention of jaundice or hepatitis).

- Foot EC, Thomson WB. Cholestatic jaundice after chloramphenicol. Br Med J 1963; 1 (5327): 403-4. [PMC free article: PMC2123872] [PubMed: 13958656](54 year old man developed jaundice two months after starting intermittent chloramphenicol for urinary tract infections [bilirubin 19 mg/dL, ALT 305 U/L, Alk P 2.3 times ULN], with subsequent pancytopenia and death from sepsis).

- Gjone E, Orning OM. Jaundice due to chloramphenicol. Acta Hepatosplenol 1966; 13: 288-92. [PubMed: 5994989](25 year old woman developed fatigue followed by jaundice on 4 occasions over a four year period [AST 210, 2160, 2120 and 426, Alk P twice normal], each episode preceded by a course of chloramphenicol).

- Rubin E, Gottlieb C, Vogel P. Syndrome of hepatitis and aplastic anemia. Am J Med 1968; 45: 88-97. [PubMed: 5658873](Description of 9 cases of jaundice followed by pancytopenia and aplasia of unknown cause, suspected to be due to a form of viral hepatitis).

- Wallerstein RO, Condit PK, Kasper CK, Brown JW, Morrison FR. Statewide study of chloramphenicol therapy and fatal aplastic anemia. JAMA 1969; 208: 2045-50. [PubMed: 5818983](Review of death certificates and pharmacy records in California over 18 month period identified 60 deaths attributed to aplastic anemia, among whom 8 had recently received chloramphenicol representing a risk for aplastic anemia of ~1 per 36,000 persons exposed to chloramphenicol).

- Furuyama M, Matsuda I. Chloramphenicol and jaundice in a baby. Lancet 1967; 2 (7511): 366-7. [PubMed: 4143738](2 month old child developed jaundice 16 days after starting intramuscular injections of chloramphenicol [bilirubin ~4-5 mg/dL, ALT 40-75 U/L, Alk P not given], resolving rapidly after stopping antibiotic).

- Polak BC, Wesseling H, Schut D, Herxheimer A, Meyler L. Blood dyscrasias attributed to chloramphenicol. A review of 576 published and unpublished cases. Acta Med Scand 1972; 192: 409-14. [PubMed: 5083381](Analysis of 576 cases of blood dyscrasias attributed to chloramphenicol, 70% had pancytopenia, mortality was independent of age or sex; no mention of liver injury or jaundice).

- Hodgkinson R. The chloramphenicol--hepatitis--aplastic anaemia syndrome. Med J Aust 1973; 1: 939-40. [PubMed: 4715401](Five cases of aplastic anemia and hepatitis, presenting with fatigue and jaundice with aplastic anemia arising during recovery, but resulting in death over long term).

- Ito M, Fukuiya Y. [Hepatitis-aplastic anemia syndrome (after the administration of chloramphenicol) (author's transl)]. Rinsho Ketsueki 1974 Sep; 15 (9): 985-92. [PubMed: 4612200](32 year old woman developed jaundice 4 weeks after a 4 week course of chloramphenicol [bilirubin 25.2 mg/dL, ALT 1100 U/L, Alk P 1.2 times ULN], resolving over the next few weeks, but then developing thrombocytopenia followed by fatal aplastic anemia).

- Shibata A, Fukuda M. [Chloramphenicol-hepatitis-aplastic anemia syndrome]. Nihon Rinsho 1977; 35 Suppl 1: 970-1. Japanese. [PubMed: 613075]

- Casale TB, Macher AM, Fauci AS. Complete hematologic and hepatic recovery in a patient with chloramphenicol hepatitis-pancytopenia syndrome. J Pediatr 1982; 101: 1025-7. [PubMed: 7143157](15 year old boy with chronic granulomatous disease developed fever and liver injury 18 days after starting chloramphenicol for C. violaceum sepsis [bilirubin normal, ALT ~150 U/L, GGT 1160 U/L, platelets 50,000], recovering promptly with stopping).

- Yunis AA. Chloramphenicol toxicity: 25 years of research. Am J Med 1989 Sep; 87 (3N): 44N-48N. [PubMed: 2486534](Review of the metabolism of chloramphenicol and its toxicity to bone marrow elements leads to the hypothesis that a toxic metabolite of the drug is responsible for damage and loss of marrow stem cells).

- Doona M, Walsh JB. Use of chloramphenicol as topical eye medication: time to cry halt? BMJ 1995; 310 (6989): 1217-8. [PMC free article: PMC2549610] [PubMed: 7767184](Editorial suggesting avoidance of use of ophthalmologic chloramphenicol because of the rare, but fatal complication of aplastic anemia, at least 5 cases of which are described in the literature).

- Rayner SA, Buckley RJ. Ocular chloramphenicol and aplastic anaemia. Is there a link? Drug Saf 1996; 14: 273-6. [PubMed: 8800624](Review of the evidence for and against the association of chloramphenicol eye drops and aplastic anemia).

- Wiholm BE, Kelly JP, Kaufman D, Issaragrisil S, Levy M, Anderson T, Shapiro S. Relation of aplastic anaemia to use of chloramphenicol eye drops in two international case-control studies. BMJ 1998; 316 (7132): 666. [PMC free article: PMC28472] [PubMed: 9522791](Analyses of registries from two international case control studies of aplastic anemia found none of 426 cases [but 7 of 3118 controls] had a recent history of use of chloramphenicol eye drops).

- Lancaster T, Swart AM, Jick H. Risk of serious haematological toxicity with use of chloramphenicol eye drops in a British general practice database. BMJ 1998; 316: 667. [PMC free article: PMC28473] [PubMed: 9522792](Among 442,543 patients who received chloramphenicol eye drops over a 7 year period in the UK, 3 patients had a subsequent diagnosis of severe hematologic toxicity within the following 3 months, but in each case an alternative diagnosis was possible and the maximal calculated risk was <1 per 100,000 persons exposed).

- Wareham DW, Wilson P. Chloramphenicol in the 21st century. Hosp Med 2002; 63 (3): 157-61. [PubMed: 11933819](Review of the current status of chloramphenicol as an antiinfective agent as well as its spectrum of activity, mechanism of action, pharmacokinetics, adverse effects, interactions and clinical uses).

- Doshi B, Sarkar S. Topical administration of chloramphenicol can induce acute hepatitis. BMJ 2009; 338: 1699. [PubMed: 19525305](37 year old man developed fatigue and jaundice, 1 week after a 5 day course of chloramphenicol eye drops [bilirubin 1.9 mg/dL, AST 868 U/L, Alk P 224 U/L], resolving over the next 10 months).

- PMCPubMed Central citations

- PubChem SubstanceRelated PubChem Substances

- PubMedLinks to PubMed

- Review Aplastic anemia associated with parenteral chloramphenicol: review of 10 cases, including the second case of possible increased risk with cimetidine.[Rev Infect Dis. 1988]Review Aplastic anemia associated with parenteral chloramphenicol: review of 10 cases, including the second case of possible increased risk with cimetidine.West BC, DeVault GA Jr, Clement JC, Williams DM. Rev Infect Dis. 1988 Sep-Oct; 10(5):1048-51.

- CHLORAMPHENICOL TOXICITY IN LIVER AND RENAL DISEASE.[Arch Intern Med. 1963]CHLORAMPHENICOL TOXICITY IN LIVER AND RENAL DISEASE.SUHRLAND LG, WEISBERGER AS. Arch Intern Med. 1963 Nov; 112:747-54.

- Fatal aplastic anemia following topical administration of ophthalmic chloramphenicol.[Am J Ophthalmol. 1982]Fatal aplastic anemia following topical administration of ophthalmic chloramphenicol.Fraunfelder FT, Bagby GC Jr, Kelly DJ. Am J Ophthalmol. 1982 Mar; 93(3):356-60.

- Review Drug-induced anaemias.[Drugs. 1976]Review Drug-induced anaemias.Girdwood RH. Drugs. 1976; 11(5):394-404.

- [FATAL APLASTIC ANEMIA FOLLOWING CHLORAMPHENICOL MEDICATION].[Harefuah. 1964][FATAL APLASTIC ANEMIA FOLLOWING CHLORAMPHENICOL MEDICATION].LURIE I, PRUSAK Y. Harefuah. 1964 Jan 15; 66:53-5.

- Chloramphenicol - LiverToxChloramphenicol - LiverTox

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

See more...