NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012-.

LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet].

Show detailsOVERVIEW

Introduction

Trimethobenzamide is an orally available, antiemetic agent used in the therapy of nausea and vomiting associated with medications and gastrointestinal, viral and other illnesses. Trimethobenzamide has not been linked convincingly to elevations in serum enzymes during therapy and despite widescale use for almost 50 years, it has rarely been linked to instances of clinically apparent liver injury with jaundice.

Background

Trimethobenzamide (trye meth” oh ben’ za mide) is a benzamide used to prevent nausea and vomiting. Its mechanism of action is uncertain, but it is believed to act directly on the central chemoreceptor nausea trigger zone of the medulla oblongata of the brain. It has weak antihistaminic activity, but does not appear to act via serotonin or dopamine pathways. Trimethobenzamide was approved for use in the United States in 1974 and is widely used in therapy of nausea, vomiting caused by gastroenteritis, medications and other illnesses. Trimethobenzamide is available as 300 mg capsules in generic forms and under the brand name Tigan. It is also available as a solution for injection (100 mg/mL). Trimethobenzamide used to be available also as suppositories, but this formulation was discontinued due to lack of efficacy. The typical oral dose of trimethobenzamide for in adults is 300 mg three or four times a day as needed, usually for short periods only. Intravenous formulations are used for therapy of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Common side effects include drowsiness, dizziness, headache, fatigue, diarrhea and polyuria. Rare side effects include hypersensitivity reactions, skin rash, disorientation, acute dystonic reactions and extrapyramidal symptoms including muscle spasms of the neck and tongue, opisthotonos, restlessness an akinesia.

Hepatotoxicity

Serum aminotransferase elevations during trimethobenzamide therapy are uncommon and rates of such elevations have not been reported in large clinical trials. A single case report of hepatitis and jaundice attributed to trimethobenzamide was published in 1967 that predated availability of tests for hepatitis A, B and C and of modern imaging studies. The latency to onset was approximately 2 weeks and the pattern of injury was mixed. There were no immunoallergic or autoimmune features and recovery was prompt once the medication was stopped. Since that report, there has only been a single mention of possible hepatotoxicity due to trimethobenzamide, a somewhat prolonged case of hepatocellular injury with a cholestatic pattern on liver biopsy despite minimal jaundice. Thus, clinically apparent liver injury from trimethobenzamide must be very rare and is generally mild and self-limited in course.

Likelihood score: D (possible rare cause of clinically apparent liver injury).

Mechanism of Injury

Trimethobenzamide is metabolized in the liver but appears to have few drug-drug interactions. The mechanism by which it might cause liver injury is unknown.

Outcome and Management

The hepatic injury caused by trimethobenzamide is usually mild and reversible with stopping the medication. Trimethobenzamide has not been linked to cases of acute liver failure, chronic hepatitis or vanishing bile duct syndrome. There is no information about possible cross sensitivity to liver injury with other antiemetics or antihistamines. In view of the many other antiemetics available, rechallenge with trimethobenzamide is not necessary and should be avoided.

Drug Class: Gastrointestinal Agents, Antiemetics

PRODUCT INFORMATION

REPRESENTATIVE TRADE NAMES

Trimethobenzamide – Generic, Tigan®

DRUG CLASS

Gastrointestinal Agents

Product labeling at DailyMed, National Library of Medicine, NIH

CHEMICAL FORMULA AND STRUCTURE

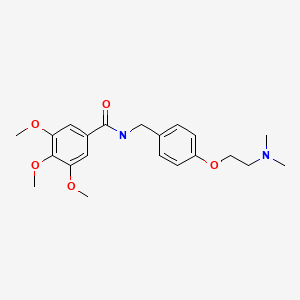

| DRUG | CAS REGISTRY NO. | MOLECULAR FORMULA | STRUCTURE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trimethobenzamide | 138-56-7 | C21-H28-N2-O5 |

|

ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY

References updated: 03 September 2020

- Zimmerman HJ. Antiemetic and prokinetic compounds. Miscellaneous drugs and diagnostic chemicals. In, Zimmerman, HJ. Hepatotoxicity: the adverse effects of drugs and other chemicals on the liver. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1999: pp. 721.(Expert review of hepatotoxicity published in 1999 lists trimethobenzamide as having caused a single case of cholestatic liver injury [Borda and Jick: 1987]).

- Sharkey KA, MacNaughton. Antinauseants and antiemetics: Gastrointestinal motility and water flux, emesis, and biliary and pancreatic disease. In, Brunton LL, Hilal-Dandan R, Knollman BC, eds. Goodman & Gilman's the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 13th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2018, pp. 934-8.(Textbook of pharmacology and therapeutics).

- Brandman O. Clinical evaluation of the effectiveness and safety of trimethobenzamide (tigan). Gastroenterology. 1960;38:777–80. [PubMed: 13803875](Among 50 adults with nausea and vomiting of different causes given a single dose of trimethobenzamide [100 mg orally or intramuscularly], 84% appeared to benefit, and no adverse side effects were observed).

- Wolfson B, Torres-Kay M, Foldes FF. Investigation of the usefulness of trimethobenzamide (Tigan) for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 1962;41:172–7. [PubMed: 14008063](Among 870 patients undergoing surgery and anesthesia treated with intramuscular trimethobenzamide vs placebo, "side effects attributable to trimethobenzamide were not observed").

- Coppolino CA, Wallace G. Trimethobenzamide antiemetic in immediate postoperative period. Double-blind study in 2,000 cases. JAMA. 1962;180:326–8. [PubMed: 13881235](Among 2000 patients scheduled for elective surgery given intramuscular injections of trimethobenzamide or placebo, nausea was less in the trimethobenzamide treated subjects; no mention of side effects).

- Moertel CG, Reitemeier RJ, Gage RP. A controlled clinical evaluation of antiemetic drugs. JAMA. 1963;186:116–8. [PubMed: 14056524](Among 300 patients with cancer receiving fluorouracil who were randomized to receive one of 6 oral antiemetic regimens, the only "significant" side effect was over sedation, which occurred in 8% given prochlorperazine but 0% on trimethobenzamide).

- Nichamin SJ. Severe allergic reaction to an antiemetic trimethobenzamide hydrochloride (Tigan). Harper Hosp Bull. 1964 Jan-Feb;22:2–5. [PubMed: 14103491](4 year old boy developed abdominal pain, arthritis and facial edema a few hours after an intramuscular injection of trimethobenzamide [8% eosinophilia, no liver tests reported], resolving within 3-4 days with epinephrine and diphenhydramine).

- Bardfeld PA. A controlled double-blind study of trimethobenzamide, prochlorperazine, and placebo. JAMA. 1966;196:796–8. [PubMed: 5326281](Among 126 patients with nausea or vomiting of various causes treated with intramuscular injections of trimethobenzamide, prochlorperazine or placebo, drowsiness occurred in 12% and dizziness in 2% of trimethobenzamide treated patients, but no other adverse events were recorded).

- Borda I, Jick H. Hepatitis following the administration of trimethobenzamide hydrochloride. Arch Intern Med. 1967;120:371–3. [PubMed: 6038296](50 year old woman with breast cancer receiving irradiation therapy developed jaundice 2 weeks after starting oral trimethobenzamide for prevention of nausea [bilirubin 15.3 mg/dL, ALT 330 U/L, Alk P 14.3 Sigma units], resolving within the following month).

- Hurley JD, Eshelman FN. Trimethobenzamide HCl in the treatment of nausea and vomiting associated with antineoplastic chemotherapy. J Clin Pharmacol. 1980;20:352–6. [PubMed: 7400373](Among 55 patients receiving cancer chemotherapy given intramuscular injections of trimethobenzamide or placebo four times daily for 48 hours, "no side effects attributable to trimethobenzamide were recorded").

- Chalasani N, Fontana RJ, Bonkovsky HL, Watkins PB, Davern T, Serrano J, Yang H, Rochon J., Drug Induced Liver Injury Network (DILIN). Causes, clinical features, and outcomes from a prospective study of drug-induced liver injury in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1924–34. [PMC free article: PMC3654244] [PubMed: 18955056](Among 300 cases of drug induced liver disease in the US collected between 2004 and 2008, no cases were attributed to an antiemetic).

- Reuben A, Koch DG, Lee WM., Acute Liver Failure Study Group. Drug-induced acute liver failure: results of a U.S. multicenter, prospective study. Hepatology. 2010;52:2065–76. [PMC free article: PMC3992250] [PubMed: 20949552](Among 1198 patients with acute liver failure enrolled in a US prospective study between 1998 and 2007, 133 were attributed to drug induced liver injury, but none were attributed to antiemetic agents).

- Ferrajolo C, Capuano A, Verhamme KM, Schuemie M, Rossi F, Stricker BH, Sturkenboom MC. Drug-induced hepatic injury in children: a case/non-case study of suspected adverse drug reactions in VigiBase. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;70:721–8. [PMC free article: PMC2997312] [PubMed: 21039766](Among 624,673 adverse event reports in children between 2000 and 2006 in the WHO VigiBase, 1% were hepatic, but no antiemetic was listed among the 41 most commonly implicated agents).

- Björnsson ES, Bergmann OM, Björnsson HK, Kvaran RB, Olafsson S. Incidence, presentation and outcomes in patients with drug-induced liver injury in the general population of Iceland. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1419–25. [PubMed: 23419359](In a population based study of drug induced liver injury from Iceland, 96 cases were identified over a 2 year period, but none were attributed to antiemetics).

- Hernández N, Bessone F, Sánchez A, di Pace M, Brahm J, Zapata R, A, Chirino R, et al. Profile of idiosyncratic drug induced liver injury in Latin America. An analysis of published reports. Ann Hepatol. 2014;13:231–9. [PubMed: 24552865](Systematic review of literature of drug induced liver injury in Latin American countries published from 1996 to 2012 identified 176 cases, the most common implicated agents being nimesulide [n=53: 30%], cyproterone [n=18], nitrofurantoin [n=17], antituberculosis drugs [n=13] and flutamide [n=12: 7%]; no antiemetic was listed).

- Chalasani N, Bonkovsky HL, Fontana R, Lee W, Stolz A, Talwalkar J, Reddy KR, et al. United States Drug Induced Liver Injury Network. Features and outcomes of 899 patients with drug-induced liver injury: The DILIN Prospective Study. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:1340–52.e7. [PMC free article: PMC4446235] [PubMed: 25754159](Among 899 cases of drug induced liver injury enrolled in a US prospective study between 2004 and 2013, none were attributed to trimethobenzamide).

- Siddique AS, Siddique O, Einstein M, Urtasun-Sotil E, Ligato S. Drug and herbal/dietary supplements-induced liver injury: a tertiary care center experience. World J Hepatol. 2020;12:207–19. [PMC free article: PMC7280859] [PubMed: 32547688](Among 600 patients who underwent liver biopsy for unexplained rise in serum enzymes over a 5 year period, drug induced liver injury accounted for 38 days, one of which was attributed to trimethobenzamide [bilirubin 15 mg/dL, ALT 630 U/L, Alk P 135 U/L], with a cholestatic hepatitis on biopsy and a prolonged course).

- PMCPubMed Central citations

- PubChem SubstanceRelated PubChem Substances

- PubMedLinks to PubMed

- Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of trimethobenzamide to control nausea and vomiting during initiation and continued treatment with subcutaneous apomorphine injection.[Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2014]Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of trimethobenzamide to control nausea and vomiting during initiation and continued treatment with subcutaneous apomorphine injection.Hauser RA, Isaacson S, Clinch T, Tigan/Apokyn Study Investigators. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2014 Nov; 20(11):1171-6. Epub 2014 Aug 27.

- Review Rolapitant.[LiverTox: Clinical and Researc...]Review Rolapitant.. LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury. 2012

- How to manage the initiation of apomorphine therapy without antiemetic pretreatment: A review of the literature.[Clin Park Relat Disord. 2023]How to manage the initiation of apomorphine therapy without antiemetic pretreatment: A review of the literature.Isaacson SH, Dewey RB Jr, Pahwa R, Kremens DE. Clin Park Relat Disord. 2023; 8:100174. Epub 2022 Dec 19.

- Trimethobenzamide HCl in the treatment of nausea and vomiting associated with antineoplastic chemotherapy.[J Clin Pharmacol. 1980]Trimethobenzamide HCl in the treatment of nausea and vomiting associated with antineoplastic chemotherapy.Hurley JD, Eshelman FN. J Clin Pharmacol. 1980 May-Jun; 20(5-6 Pt 1):352-6.

- Review Dronabinol.[LiverTox: Clinical and Researc...]Review Dronabinol.. LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury. 2012

- Trimethobenzamide - LiverToxTrimethobenzamide - LiverTox

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

See more...