NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012-.

LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet].

Show detailsOVERVIEW

Introduction

Nicotine is a natural alkyloid that is a major component of cigarettes and is used therapeutically to help with smoking cessation. Nicotine has not been associated with liver test abnormalities or with clinically apparent hepatotoxicity.

Background

Nicotine (nik' oh teen) is a liquid alkyloid that has a variety of activities in the body and central nervous system (CNS), acting largely as a stimulant via activation of nicotinic receptors. Nicotine is a CNS stimulant and has both stimulatory and depressant actions on autonomic ganglia. Nicotine has multiple actions including CNS stimulation, elation, wakefulness and appetite suppression. It also causes dependency and addiction accounting for the difficulty of smoking cessation. Indeed, the major medical use of nicotine is to help to stop smoking. Oral and transdermal forms of nicotine have been shown to increase the rate of smoking cessation. Nicotine is readily absorbed through the skin, mucous membranes and lungs. Oral nicotine can be taken as a gum (Nicorette: 2 or 4 mg each), or lozenge (2 or 4 mg) which is dissolved in the mouth and not swallowed or chewed. Nasal spray, inhaler (Nicotrol) and transdermal formulations (NicoDerm, Habitrol and others) are also used in smoking cessation programs. Most of these products are available over the counter, without prescription. The usual dose regimen varies by formulation and the dose is typically given in decreasing amounts with cigarette withdrawal. Cigarettes typically have 10 to 25 mg of nicotine each, and peak plasma nicotine levels are higher with cigarettes than with replacement products. Common side effects of nicotine include nausea, dyspepsia, nervousness, dizziness, headache, tachycardia and palpitations. Overdose of nicotine can cause mental confusion, faintness, hypotension, convulsions and respiratory failure.

Starting in 2006, electronic nicotine delivery systems (e-cigarettes) became available in the United States. The typical e-cigarette includes a lithium battery, a heating coil and a solute chamber that contains a liquid solution of nicotine typically suspended in propylene glycol with flavors and other ingredients. The heating coil creates a nicotine vapor (and thus called “vaping”) that is inhaled through a mouthpiece. E-cigarettes were promoted as a means of smoking cessation, but in prospective controlled trials they were only minimally more effective than conventional nicotine replacement or other pharmacological therapies. Furthermore, the majority of subjects who were able to stop smoking by using e-cigarettes continued vaping use long term, thus serving as a smoking replacement. While e-cigarettes have been shown to contain fewer and less potential harmful compounds, they cannot be considered entirely safe. Furthermore, many individuals and particularly teenagers who have not previously smoked have begun vaping and often using flavored or cannabinoid based products. While e-cigarettes have fewer adverse effects than conventional cigarettes, they have been linked to rare but potentially severe adverse events include vaping associated lung injury that appears to be caused by use of vitamin E acetate as a solvent for nicotine and cannabinoid solutions.

Hepatotoxicity

Nicotine used in cigarette cessation programs as well as nicotine containing e-cigarettes have not been associated with serum enzyme elevations during therapy at rates greater than occurred with placebo. Medical and recreational uses of nicotine have not been associated with cases of clinically apparent liver injury.

Likelihood score: E (unlikely cause of clinically apparent liver injury).

Mechanism of Injury

Nicotine is metabolized extensively by many tissues including the liver and is rapidly excreted.

[Agents in clinical use to aid in smoking cessation and to treat nicotine withdrawal symptoms include bupropion, nicotine, and varenicline.]

Drug Class: Substance Abuse Treatment Agents

PRODUCT INFORMATION

REPRESENTATIVE TRADE NAMES

Nicotine – Generic, Commit®, Nicorette® (Oral); Habitrol® (Transdermal); Nicotrol® (Inhaler, Spray)

DRUG CLASS

Substance Abuse Treatment Agents

Product labeling at DailyMed, National Library of Medicine, NIH

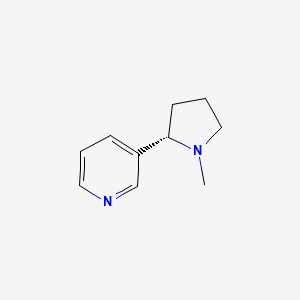

CHEMICAL FORMULA AND STRUCTURE

| DRUG | CAS REGISTRY NUMBER | MOLECULAR FORMULA | STRUCTURE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nicotine | 54-11-5 | C10-H14-N2 |

|

ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY

References updated: 25 March 2020

- Zimmerman HJ. Hepatotoxicity: the adverse effects of drugs and other chemicals on the liver. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1999.(Expert review of hepatotoxicity published in 1999; nicotine is not discussed).

- Hibbs RE, Zambon AC. Nicotine. Agents acting at the neuromuscular junction and autonomic ganglia. In, Brunton LL, Hilal-Dandan R, Knollman BC, eds. Goodman & Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 13th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2018, pp 177-90.(Textbook of pharmacology and therapeutics).

- O'Brien CP. Nicotine. Drug addiction and drug abuse. In, Brunton LL, Hilal-Dandan R, Knollman BC, eds. Goodman & Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 13th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2018, pp 437-9.(Textbook of pharmacology and therapeutics).

- Molyneux A. Nicotine replacement therapy. BMJ. 2004;328:454–6. [PMC free article: PMC344271] [PubMed: 14976103](Review of nicotine replacement therapy including mechanism of action, evidence of effectiveness, formulations, and safety; choice of product should be by patient preference; the products are safer than cigarettes and the only safety concerns relate to pregnant women and patients with heart disease).

- Marsh HS, Dresler CM, Choi JH, Targett DA, Gamble ML, Strahs KR. Safety profile of a nicotine lozenge compared with that of nicotine gum in adult smokers with underlying medical conditions: a 12-week, randomized, open-label study. Clin Ther. 2005;27:1571–87. [PubMed: 16330293](901 smokers with other medical conditions [mostly heart disease and diabetes] were treated with nicotine gum or lozenges for 12 weeks; nausea, hiccups and headache were the most common side effects; no mention of hepatotoxicity, but no instances of acute liver injury).

- Dautzenberg B, Nides M, Kienzler JL, Callens A. Pharmacokinetics, safety and efficacy from randomized controlled trials of 1 and 2 mg nicotine bitartrate lozenges (Nicotinell). BMC Clin Pharmacol. 2007;7:11. [PMC free article: PMC2194660] [PubMed: 17922899](Use of nicotine lozenges even in higher than recommended amounts was not associated with any "clinically significant changes" in serum enzyme levels).

- Shiffman S, Sweeney CT. Ten years after the Rx-to-OTC switch of nicotine replacement therapy: what have we learned about the benefits and risks of non-prescription availability? Health Policy. 2008;86:17–26. [PubMed: 17935827](Systematic review of literature and adverse event reporting on nicotine replacement therapy, which has been marketed "without incident as a non-prescription product in 33 countries...").

- Moore D, Aveyard P, Connock M, Wang D, Fry-Smith A, Barton P. Effectiveness and safety of nicotine replacement therapy assisted reduction to stop smoking: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2009;338:b1024. [PMC free article: PMC2664870] [PubMed: 19342408](Systematic review of literature on efficacy and safety of nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation; no serious adverse events were attributed to nicotine therapy; no mention of liver injury or ALT levels).

- Ossip DJ, Abrams SM, Mahoney MC, Sall D, Cummings KM. Adverse effects with use of nicotine replacement therapy among quitline clients. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11:408–17. [PubMed: 19325134](Follow up interviews were conducted on 33,690 smokers who were given nicotine replacement therapy; 25% reported adverse events, but these were largely nonspecific and mild, without mention of liver injury).

- Safety of smoking cessation drugs. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2009;51(1319):65. [PubMed: 19696706](Concise review of safety of medications used for smoking cessation; nicotine replacement therapy is not discussed).

- McNeil JJ, Piccenna L, Ioannides-Demos LL. Smoking cessation-recent advances. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2010;24:359–67. [PubMed: 20602163](Review of mechanisms of action, efficacy and safety of smoking cessation therapies; hepatotoxicity is not discussed).

- Bullen C, Howe C, Laugesen M, McRobbie H, Parag V, Williman J, Walker N. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;382:1629–37. [PubMed: 24029165](Among 657 adult smokers treated for smoking cessation for 12 weeks, confirmed abstinence rates at 24 weeks was 5.8% for a nicotine patch, 7.3% for e-cigarettes and 4.3% for placebo e-cigarettes; adverse event rates were similar across groups and there were no serious adverse events attributed to the interventions).

- Hajek P, Etter JF, Benowitz N, Eissenberg T, McRobbie H. Electronic cigarettes: review of use, content, safety, effects on smokers and potential for harm and benefit. Addiction. 2014;109:1801–10. [PMC free article: PMC4487785] [PubMed: 25078252](Review of the use, content, efficacy and safety of e-cigarettes concludes that they are a reasonable option for smokers unable to quit using conventional approaches, as a safer alternative to smoking and a possible pathway to complete cessation).

- Pisinger C, Døssing M. A systematic review of health effects of electronic cigarettes. Prev Med. 2014;69:248–60. [PubMed: 25456810](Systematic review of the literature identified 74 articles on health effects of e-cigarettes some focusing upon ingredients showing variability in concentrations of nicotine, propylene glycol and low levels of nitrosamines, formaldehyde, toluene, chromium and cinnamon, the products frequently showing cytotoxicity in cell culture systems; human studies being few and frequently biased; the authors concluded that e-cigarettes could hardly be considered harmless).

- Crowley RA., Health Public Policy Committee of the American College of Physicians. Electronic nicotine delivery systems: executive summary of a policy position paper from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:583–4. [PubMed: 25894027](Recommendations regarding e-cigarettes from the American College of Physicians include that they be regulated by the FDA, that flavoring be banned, that they be taxed to discourage use, that their promotion be regulated, that their use be restricted in public places and that increased funding be given to research on their safety).

- Kaisar MA, Prasad S, Liles T, Cucullo L. A decade of e-cigarettes: limited research & unresolved safety concerns. Toxicology. 2016;365:67–75. [PMC free article: PMC4993660] [PubMed: 27477296](Review of the safety of e-cigarettes, a decade after they first became available during which there has been a marked increase in their use particularly among teenagers).

- Walele T, Sharma G, Savioz R, Martin C, Williams J. A randomised, crossover study on an electronic vapour product, a nicotine inhalator and a conventional cigarette. Part B: Safety and subjective effects. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2016;74:193–9. [PubMed: 26702788](Short term study of safety of electronic vapor nicotine delivery system compared to conventional cigarettes and a nicotine inhalator found no serious adverse events and similar tolerance among the various products tested).

- Dinakar Ch, O’Connor GT. The health effects of electronic cigarettes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2608–9. [PubMed: 28029910](Review of the health benefits and risks of e-cigarettes whether used short term as a smoking cessation aid or long term as a smoking replacement; no mention of liver injury).

- Breland A, Soule E, Lopez A, Ramôa C, El-Hellani A, Eissenberg T. Electronic cigarettes: what are they and what do they do? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2017;1394:5–30. [PMC free article: PMC4947026] [PubMed: 26774031](Review of the design of commercially available e-cigarettes, their ingredients, clinical efficacy in smoking cessation, problems of use in previous nonsmokers and laboratory evidence for effects on respiratory, cardiovascular and immune function; no mention of hepatic effects).

- Canistro D, Vivarelli F, Cirillo S, Babot Marquillas C, Buschini A, Lazzaretti M, Marchi L, et al. E-cigarettes induce toxicological effects that can raise the cancer risk. Sci Rep. 2017;7:2028. [PMC free article: PMC5435699] [PubMed: 28515485](Studies of vapor from e-cigarettes in a rat model found evidence that they can induce potentially harmful bioactivating enzymes in lung, with formation of reactive oxygen species, DNA oxidation and DNA strand breaks suggesting that e-cigarettes may have carcinogenic effects).

- Manzoli L, Flacco ME, Ferrante M, La Vecchia C, Siliquini R, Ricciardi W, Marzuillo C, et al. ISLESE Working Group. Cohort study of electronic cigarette use: effectiveness and safety at 24 months. Tob Control. 2017;26:284–92. [PMC free article: PMC5520273] [PubMed: 27272748](Follow up of 24 months found rates of not smoking to be 61% among smokers who switched to e-cigarettes, 23% among smokers who did not use e-cigarettes and 25% among those who used both, with no differences in adverse event rates).

- Drugs for smoking cessation. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2019;61(1576):105–10. [PubMed: 31381546](Concise review of the mechanism of action, clinical efficacy and safety of drugs used for smoking cessation mentions that e-cigarettes are not approved for use in smoking cessation by the FDA and that their potential for causing long term adverse effects is not known).

- Hajek P, Phillips-Waller A, Przulj D, Pesola F, Myers Smith K, Bisal N, Li J, et al. A randomized trial of e-cigarettes versus nicotine-replacement therapy. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:629–37. [PubMed: 30699054](Among 886 who wanted to stop smoking and were randomized to nicotine replacement therapy or e-cigarettes, smoking abstinence at 12 months was 10% vs 18%, but 80% of the e-cigarette compared to only 9% of the nicotine replacement group were still using the product; no mention of ALT elevations or hepatotoxicity).

- Civiletto CW, Aslam S, Hutchison J. Electronic delivery (vaping) of cannabis and nicotine. November 10, 2019. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020. http://www

.ncbi.nlm.nih .gov/books/NBK545160/ (Review of modern electronic cigarette design, their increasing use, effects and safety focusing upon acute and chronic lung injury). - Blount BC, Karwowski MP, Shields PG, Morel-Espinosa M, Valentin-Blasini L, Gardner M, Braselton M, et al. Lung Injury Response Laboratory Working Group. Vitamin E acetate in bronchoalveolar-lavage fluid associated with EVALI. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:697–705. [PMC free article: PMC7032996] [PubMed: 31860793](Analysis of bronchial lavage samples from 50 patients with severe e-cigarette vaping associated lung injury revealed vitamin E acetate in 41, suggesting that aerosolization of the solvent was responsible for the tissue injury).

- PMCPubMed Central citations

- PubChem SubstanceRelated PubChem Substances

- PubMedLinks to PubMed

- Smoking cessation medicines and e-cigarettes: a systematic review, network meta-analysis and cost-effectiveness analysis.[Health Technol Assess. 2021]Smoking cessation medicines and e-cigarettes: a systematic review, network meta-analysis and cost-effectiveness analysis.Thomas KH, Dalili MN, López-López JA, Keeney E, Phillippo D, Munafò MR, Stevenson M, Caldwell DM, Welton NJ. Health Technol Assess. 2021 Oct; 25(59):1-224.

- Correlates of use of electronic cigarettes versus nicotine replacement therapy for help with smoking cessation.[Addict Behav. 2014]Correlates of use of electronic cigarettes versus nicotine replacement therapy for help with smoking cessation.Pokhrel P, Little MA, Fagan P, Kawamoto CT, Herzog TA. Addict Behav. 2014 Dec; 39(12):1869-73. Epub 2014 Aug 7.

- Review Interventions to reduce harm from continued tobacco use.[Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016]Review Interventions to reduce harm from continued tobacco use.Lindson-Hawley N, Hartmann-Boyce J, Fanshawe TR, Begh R, Farley A, Lancaster T. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Oct 13; 10(10):CD005231. Epub 2016 Oct 13.

- The Role of Nicotine Dependence in E-Cigarettes' Potential for Smoking Reduction.[Nicotine Tob Res. 2018]The Role of Nicotine Dependence in E-Cigarettes' Potential for Smoking Reduction.Selya AS, Dierker L, Rose JS, Hedeker D, Mermelstein RJ. Nicotine Tob Res. 2018 Sep 4; 20(10):1272-1277.

- Review E-cigarettes and smoking cessation: evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis.[PLoS One. 2015]Review E-cigarettes and smoking cessation: evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis.Rahman MA, Hann N, Wilson A, Mnatzaganian G, Worrall-Carter L. PLoS One. 2015; 10(3):e0122544. Epub 2015 Mar 30.

- Nicotine - LiverToxNicotine - LiverTox

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

See more...