NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012-.

LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet].

Show detailsOVERVIEW

Introduction

Mepacrine (also known as quinacrine and atabrine) is an acridine derivative initially used in the therapy and prevention of malaria and later as an antiprotozoal and immunomodulatory agent. Mepacrine causes a yellowing of the sclera that is not due to liver injury, but also can cause serum enzyme elevations during therapy (particularly in high doses) and has been linked to rare instances of clinically apparent acute liver injury which can be severe and has resulted in fatalities.

Background

Mepacrine, also known as quinacrine (kwin' a crin) or atabrine, is an acridine derivative that was developed in the 1920s and extensively used as an antimalarial agent by the U.S. military in the South Pacific during World War II. It was recognized as causing a yellowing of the skin that resembled jaundice, but had few serious side effects, particularly at the low doses used for prophylaxis against malaria. Mepacrine was subsequently replaced by chloroquine and other more effective and better tolerated agents for malaria. Mepacrine also has activity against Giardia lamblia parasites as well as antiinflammatory and immunomodulatory activity, but is not approved for use in these conditions in the United States. Mepacrine continues to be used off-label, however, in lupus erythematosus, particularly for the dermatologic manifestations. While not commercially available or approved for use in the United States, mepacrine can be obtained overseas, via the internet and in some compounding pharmacies. The typical dose is 100 mg daily, and it is often combined with hydroxychloroquine, an accepted and widely used agent for rheumatologic disorders. Side effects of mepacrine are not uncommon, but are generally mild including fatigue, abdominal discomfort, cramps, nausea, diarrhea, headache and dizziness. In high doses, mepacrine causes yellowing of the skin that can be mistaken for jaundice. It has occasionally been used to induce factitious illness. Serious side effects include lichen planus, exfoliative dermatitis and aplastic anemia.

Hepatotoxicity

Mepacrine has been reported to cause elevations in serum enzymes, but the frequency of such changes is unknown, arising after 1 to 6 weeks with a mixed pattern of enzyme elevations and resolving within 1 to 2 months of stopping. Most patients are asymptomatic and liver enzyme elevations can resolve with, and sometimes without dose modification. Clinically apparent liver injury from mepacrine has also been reported, but the clinical features of the injury have not been well defined. Because mepacrine causes a yellowing of the skin, jaundice is not a reliable finding and most reports of liver injury from mepacrine have not included bilirubin elevations. Nevertheless, several instances of acute liver failure and death have been attributed to mepacrine therapy, although the reports usually predated the availability of tests for hepatitis A, B and C and often lacked histological documentation. Mepacrine has also been implicated in cases of aplastic anemia and in hypersensitivity reactions with exfoliative dermatitis, suggestive of Stevens Johnson syndrome, conditions that can be associated with liver injury that may be severe.

Likelihood score: E* (unproven but suspected cause of clinically apparent liver injury).

Mechanism of Liver Injury

The mechanism of mepacrine hepatotoxicity is not known, but likely to be due to an idiosyncratic reaction to an intermediate of its metabolism. Mepacrine has a prolonged half-life and is highly protein bound. It is preferentially taken up by the skin and liver, but details of its metabolism have not been defined.

Outcome and Management

Most instances of liver injury attributed to mepacrine have been mild, with nonspecific symptoms and serum enzyme elevations without jaundice. The liver test abnormalities resolve rapidly with stopping therapy. There is no reason to suspect that there is cross sensitivity to hepatotoxicity between mepacrine and other antimalarial agents. Mepacrine has no structural similarity to chloroquine and other antimalarial drugs.

Drug Class: Antimalarial Agents

CASE REPORT

Case 1. Serum aminotransferase elevations during mepacrine therapy.

[Modified from: Gibb W, Isenberg DA, Snaith ML. Mepacrine induced hepatitis. Ann Rheum Dis 1985; 44: 861-2. PubMed Citation]

A 37 year old woman with an undifferentiated connective tissue disorder and features of lupus erythematosus developed fatigue, anorexia, pruritus and yellowing of the skin and eyes six weeks after starting mepacrine in an initial dose of 100 mg daily that was then increased to 300 mg daily. Previous trials of hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine had been unsuccessful and associated with side effects of nausea and blurred vision. She had no history of liver disease or alcohol abuse, and liver tests had been normal in the past. Her other medical conditions included migraine headaches, asthma and recurrent bronchitis. Other medications were not mentioned. Mepacrine was stopped, but 4 weeks later she was found to have abnormal liver tests. Serum bilirubin was 0.3 mg/dL, ALT 210 U/L, AST 107 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 160 U/L and GGT 264 U/L. She had a mild eosinophilia of 680 cells per μL. Tests for hepatitis A, B and cytomegalovirus were negative. Liver tests gradually improved and were normal two months later. Skin and sclera remained yellow for two months after mepacrine was stopped.

Key Points

| Medication: | Mepacrine (300 mg daily) |

| Pattern: | Mixed (R=~3.8) |

| Severity: | 1+ (symptoms and enzyme elevations, but no jaundice) |

| Latency: | 6 weeks |

| Recovery: | 2 months |

| Other medications: | None mentioned |

Comment

A woman with a lupus-like illness who was intolerant of hydroxychloroquine was switched to mepacrine and developed nonspecific symptoms, and was found to have yellowing of the skin, suggesting significant liver injury. Laboratory testing, however, showed a normal serum bilirubin and only moderate serum aminotransferase elevations. She improved upon stopping mepacrine. While the systemic symptoms (fatigue, anorexia, itching) were likely due to the mepacrine, they may not have been due to liver injury. Fatigue is a not uncommon side effect of mepacrine therapy, particularly with the high doses that were used. Similarly, yellowing of the skin and sclera occur with high doses of mepacrine, probably because of granular deposits of mepacrine in the skin and nail beds, reflecting the yellow color of the medication itself (it is an acridine dye). The yellowish discoloration resolves within a few weeks of stopping mepacrine; the dark staining of nail beds can persist longer. While this report is widely cited as evidence of the hepatotoxicity of mepacrine, it more likely represents the frequent occurrence of nonspecific side effects and mild enzyme elevations with use of high doses. Cases of severe hepatitis with jaundice due to mepacrine have been reported, but are rare and were not well documented, occurring before the availability of tests for hepatitis A, B and C and accurate radiologic imaging of the liver. Liver injury can accompany the severe dermatologic side effects and aplastic anemia that occurs rarely with mepacrine therapy, but the liver injury is generally overshadowed by the other systemic effects.

PRODUCT INFORMATION

REPRESENTATIVE TRADE NAMES

Mepacrine – Generic

DRUG CLASS

Antimalarial Agents

Product labeling at DailyMed, National Library of Medicine, NIH

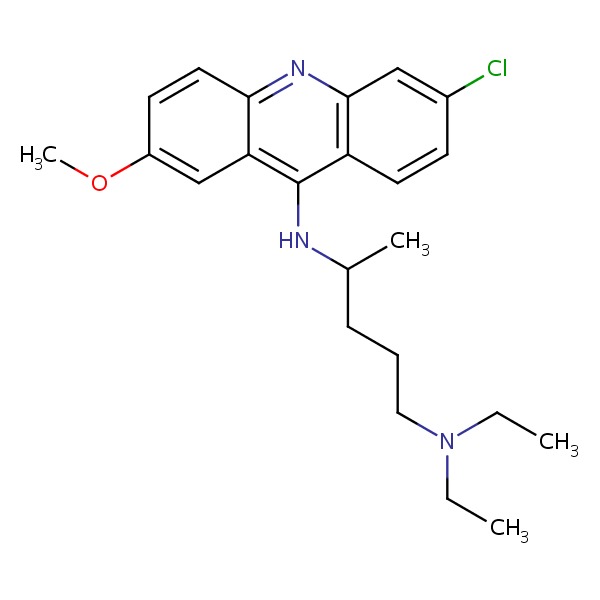

CHEMICAL FORMULA AND STRUCTURE

| DRUG | CAS REGISTRY NUMBER | MOLECULAR FORMULA | STRUCTURE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mepacrine | 83-89-6 | C23-H30-Cl-N3-O |

|

ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY

References updated: 01 February 2017

- Zimmerman HJ. Antimalarials. Hepatic injury from antimicrobial agents. In, Zimmerman HJ. Hepatotoxicity: the adverse effects of drugs and other chemicals on the liver. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1999, pp. 623.(Expert review of hepatotoxicity published in 1999; mentions that quinacrine was found to cause rare instances of hepatocellular injury when used during World War II, but rarely since, usually in the context of prolonged therapy).

- Vinetz JM, Clain J, Bounkeua V, Eastman RT, Fidock D. Chemotherapy of malaria. In, Brunton LL, Chabner B, Knollman B, eds. Goodman & Gilman's the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 12th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2011, pp. 1383-418.(Textbook of pharmacology and therapeutics).

- Livingood CS, Dieuaide FR. Untoward reactions attributable to atabrine. JAMA 1945: 129: 1091-3. Not in PubMed. [PubMed: 21004769](Summary of the dermatologic adverse reactions to atabrine focusing upon atypical lichen planus concludes that “the military value of atabrine in suppressing vivax malaria and curing falciparum malaria far outweighs untoward effects which have been attributed with reason to the use of the drug”).

- Drake JR, Moon HD. Atabrine dermatitis and associated aplastic anemia. Calif Med 1945; 65: 154-6. [PubMed: 21001532](Description of 3 types of dermatitis [lichenoid, eczematoid and exfoliative], aplastic anemia [9 cases, 7 fatal] and “acute yellow atrophy” [8 cases, 2 with dermatitis, one with aplastic anemia and 1 fatal]).

- Agress CM. Atabrine as a cause of fatal exfoliative dermatitis and hepatitis. J Am Med Assoc 1946; 131: 14-21. [PubMed: 21025602](Review of literature found no cases of hepatitis attributed to mepacrine, but authors report 5 cases with exfoliative dermatitis and some degree of hepatitis in patients receiving mepacrine for malaria; 5 Chinese men, ages 24 to 36 years, developed fever and rash within a few days of starting mepacrine with complicated subsequent courses, 3 dying of multiorgan failure and autopsies showing marked hepatic necrosis).

- Bower AG. Untoward effects of Atabrine. Calif Med 1946; 65: 157. [PMC free article: PMC1642778] [PubMed: 18731100](Short commentary mentions that the side effects of mepacrine can include nausea, nervousness, psychosis, disorientation, urticaria, exfoliative dermatitis and lichen planus; no mention of liver injury).

- Custer RP. Aplastic anemia in soldiers treated with atabrine(quinacrine). Am J Med Sci 1946; 212: 211-24. [PubMed: 20996966](“Atabrine proved superior to quinine for suppressive treatment, being more effective and better tolerated by the troops. It was generally regarded as harmless and, for the most part, with good reason.” Careful review of autopsies, however, showed an increase in aplastic anemia in atabrine treated soldiers leading to this analysis of 57 cases from the South Pacific, for an incidence of 2.8 cases per 100,000 troops, 47 received atabrine for 1-34 months, 25 had atabrine dermatitis; no mention of hepatotoxicity).

- Findlay GM. The toxicity of mepacrine in man. Trop Dis Bull 1947; 44: 763-79. [PubMed: 18906096](Extensive review of the toxicity of mepacrine focusing on lichenoid dermatitis, toxic psychosis and aplastic anemia mentions that liver lesions were found in 10 of 47 autopsied cases of aplastic anemia, with findings typical of “infective hepatitis”).

- Shumacker HB Jr, Ziperman HH. Unusual case of apparent malingering. Arch Surg 1950; 60: 861-4. [PubMed: 15411312](49 year old woman had multiple episodes of abdominal pain, fever and apparent jaundice, undergoing multiple surgical procedures without evidence of gallstones or biliary obstruction, eventually being diagnosed as having factitious illness and mepacrine induced yellowing of the skin [fabricated “jaundice”]).

- Craddock WL. Toxic hepatitis presumably produced by massive prolonged ingestion of atabrine: a case report with autopsy findings. Mil Surg 1950; 107: 199-201. [PubMed: 15438774](32 year old man who presented with jaundice and fatal variceal hemorrhage gave a history of excessive atabrine ingestion, because of unrealistic fear of malaria; no mention of alcohol use or whether cirrhosis was present and no routine liver tests provided).

- Page F. Treatment of lupus erythematosus with mepacrine. Lancet 1951; 2 (6687): 755-8. [PubMed: 14874500](Among 18 patients with lupus erythematosus treated with mepacrine [100 to 300 mg daily], all except one had a clinical response, some of which were complete; only one patient had a serious adverse event [dermatitis], but no mention of liver injury).

- Harvey G, Cochrane T. The treatment of lupus erythematosus with mepacrine (Atabrine). J Invest Dermatol 1953; 21: 99-104. [PubMed: 13084972](Among 62 patients with lupus erythematosus treated with mepacrine [usually 200 mg daily], 37 had an excellent or good response and 8 had complications, 2 with severe nausea and 6 dermatitis; no mention of liver injury).

- Rovelstad RA, Stauffer MH, Mason HL, Steinhilber RM. The simulation of jaundice by action of quinacrine (atabrine). Gastroenterology 1957; 33: 937-47. [PubMed: 13490686](Two patients with recurrent gastrointestinal symptoms and jaundice that was due to unacknowledged use of mepacrine to simulate disease, and review of literature on its hepatotoxicity).

- Marczynska-Robowska M. Acute hepatitis due to intoxication with atabrine. Helv Paediatr Acta 1960; 15: 307-9. [PubMed: 13766606](5 year old boy developed yellow skin 5 days after starting atabrine [100 mg every 3 days] for suspected malaria and was found to have high fever and jaundice 3 days later [bilirubin 10.3 mg/dL], with worsening fever, stupor and death one week later).

- Gibb W, Isenberg DA, Snaith ML. Mepacrine induced hepatitis. Ann Rheum Dis 1985; 44: 861-2. [PMC free article: PMC1001799] [PubMed: 4083944](37 year old woman with discoid lupus intolerant of chloroquine developed yellow skin and fatigue 6 weeks after starting mepacrine in a dose of 300 mg daily [bilirubin 0.3 mg/dL, ALT 210 U/L, Alk P 160 U/L, eosinophilia 688/μL], resolving within 2 months of stopping: Case 1).

- Wallace DJ. The use of quinacrine (Atabrine) in rheumatic diseases: a reexamination. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1989; 18: 282-96. [PubMed: 2658071](Extensive review of mepacrine in rheumatic disease based upon the literature and personal experience mentions that its first use in lupus was in 1939, but it became more widely used after a report in 1951 [Page], subsequently being studied in at least 20 clinical trials with 771 patients yielding beneficial responses in 73%, with onset of action after 3-4 weeks of 100 mg daily, side effects being mild and well tolerated at this dose; mentions a single report of hepatotoxicity [Gibb 1985]).

- Scoazec JY, Krolak-Salmon P, Casez O, Besson G, Thobois S, Kopp N, Perret-Liaudet A, et al. Quinacrine-induced cytolytic hepatitis in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Ann Neurol 2003; 53: 546-7. [PubMed: 12666126](3 patients with Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease developed liver test abnormalities 7, 25 and 42 days after starting 300 mg daily of mepacrine [bilirubin not given, ALT 3-30 times ULN, Alk P 2-8 times ULN], returning to normal within 3-4 weeks of stopping, subsequent autopsies showing mild lobular necrosis, portal inflammation and bile duct inflammation and fibrosis).

- Chalasani N, Bonkovsky HL, Fontana R, Lee W, Stolz A, Talwalkar J, Reddy KR, et al.; United States Drug Induced Liver Injury Network. Features and outcomes of 899 patients with drug-induced liver injury: The DILIN Prospective Study. Gastroenterology 2015; 148: 1340-52.e7. [PMC free article: PMC4446235] [PubMed: 25754159](Among 899 cases of drug induced liver injury enrolled in a US prospective study between 2004 and 2013, none were attributed to antimalarial medications or to mepacrine).

- PMCPubMed Central citations

- PubChem SubstanceRelated PubChem Substances

- PubMedLinks to PubMed

- Distribution of quinacrine (atabrine, mepacrine) in human tissues as visualized by fluorescent microscopy; considerations on the mode of action of quinacrine in lupus erythematosus.[Acta Derm Venereol. 1954]Distribution of quinacrine (atabrine, mepacrine) in human tissues as visualized by fluorescent microscopy; considerations on the mode of action of quinacrine in lupus erythematosus.MUSTAKALLIO KK. Acta Derm Venereol. 1954; 34(1-2):93-101.

- Potential Therapeutic Effects of Mepacrine against Clostridium perfringens Enterotoxin in a Mouse Model of Enterotoxemia.[Infect Immun. 2019]Potential Therapeutic Effects of Mepacrine against Clostridium perfringens Enterotoxin in a Mouse Model of Enterotoxemia.Navarro MA, Shrestha A, Freedman JC, Beingesser J, McClane BA, Uzal FA. Infect Immun. 2019 Apr; 87(4). Epub 2019 Mar 25.

- The three-dimensional hydrogen-bonded framework structure in the 1:1 proton-transfer compound of the drug quinacrine with 5-sulfosalicylic acid.[Acta Crystallogr C. 2008]The three-dimensional hydrogen-bonded framework structure in the 1:1 proton-transfer compound of the drug quinacrine with 5-sulfosalicylic acid.Smith G, Wermuth UD. Acta Crystallogr C. 2008 Aug; 64(Pt 8):o428-30. Epub 2008 Jul 12.

- Review Proguanil.[LiverTox: Clinical and Researc...]Review Proguanil.. LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury. 2012

- Review Antimalarial Agents.[LiverTox: Clinical and Researc...]Review Antimalarial Agents.. LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury. 2012

- Mepacrine - LiverToxMepacrine - LiverTox

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

See more...