NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012-.

LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet].

Show detailsOVERVIEW

Introduction

Famotidine is a histamine type 2 receptor antagonist (H2 blocker) which is commonly used for treatment of acid-peptic disease and heartburn. Famotidine has been linked to rare instances of clinically apparent acute liver injury.

Background

Famotidine (fam oh' ti deen) was the third H2 blocker introduced into clinical practice in the United States and is a commonly used agent for treatment of duodenal and gastric ulcer and gastroesophageal reflux disease. The H2 blockers are specific antagonists of the histamine type 2 receptor, which is found on the basolateral (antiluminal) membrane of gastric parietal cells. The binding of famotidine to the H2 receptor results in inhibition of acid production and secretion, and improvement in symptoms and signs of acid-peptic disease. The H2 blockers inhibit an early, “upstream” step in gastric acid production and are less potent that the proton pump inhibitors, which inhibit the final common step in acid secretion. Nevertheless, the H2 blockers inhibit 24 hour gastric acid production by about 70% and are most effective in blocking basal and nocturnal acid production. Famotidine was first approved for use in the United States in 1986 and more than 3 million prescriptions for it are filled yearly. Famotidine is now available both by prescription and over-the-counter. The listed indications for famotidine are duodenal and gastric ulcer disease, gastroesophageal reflux and prevention of stress ulcers. Famotidine is available in tablets of 20 and 40 mg in several generic forms and in parenteral forms under the brand name Pepcid. Over-the-counter formulations are typically gelcaps or tablets of 10 or 20 mg. Liquid solutions are also available for intravenous use. The typical recommended dose for therapy of peptic ulcer disease in adults is 40 mg once daily for 4 to 8 weeks and maintenance therapy of 20 mg daily. Lower, chronic and intermittent doses of famotidine are used for therapy of heartburn and indigestion. Side effects are uncommon, usually minor, and include diarrhea, constipation, fatigue, drowsiness, headache and muscle aches. Famotidine is metabolized by the hepatic cytochrome P450 system, but has minimal inhibitory effects on the metabolism of other drugs, making it less likely to cause drug-drug interactions than cimetidine.

Hepatotoxicity

Chronic therapy with famotidine has been associated with minor elevations in serum aminotransferase levels in 1% to 4% of patients, but similar rates were reported in placebo recipients. The ALT elevations are usually asymptomatic and transient, and may resolve without dose modification. Rare instances of clinically apparent liver injury have been reported in patients receiving famotidine, but few cases have been reported and clinical characteristics in published cases have varied in the time to onset and pattern of injury. Onset has ranged from 1 to 14 weeks and serum enzyme pattern has typically been hepatocellular. The injury resolves within 4 to 12 weeks of stopping famotidine. Immunoallergic features (rash, fever, eosinophilia) are uncommon, as is autoantibody formation.

Likelihood score: C (probable rare cause of clinically apparent liver injury).

Mechanism of Injury

Famotidine is metabolized by the microsomal P450 drug metabolizing enzymes and injury may be the result of its activation to a toxic intermediate.

Outcome and Management

The hepatic injury caused by famotidine is usually rapidly reversible with stopping the medication (Case 1). Famotidine has not been definitively linked to cases of acute liver failure, chronic hepatitis, prolonged cholestasis or vanishing bile duct syndrome. The results of rechallenge have not been reported. There appears to be cross reactivity in hepatic injury with cimetidine (Case 2). If acid suppression is required, use of an unrelated proton pump inhibitor is probably prudent for patients with clinically apparent famotidine induced liver injury.

The H2 receptor blockers include cimetidine, famotidine, nizatidine, and ranitidine. Combined general references on the H2 receptor blockers are given together after this overview section, while specific references are provided in the separate section on each drug. See also the Proton Pump Inhibitors.

Drug Class: Antiulcer Agents

Other Drugs in the Subclass, Histamine Type 2 Receptor Antagonists: Cimetidine, Nizatidine, Ranitidine

CASE REPORTS

Case 1. Mild acute liver injury due to famotidine.

[Modified from: Ament PW, Roth JD, Fox CJ. Famotidine-induced mixed hepatocellular jaundice. Ann Pharmacother 1994; 28: 40-2. PubMed Citation]

A 55 year old man with gastritis and abdominal pain was treated with ranitidine (150 mg twice daily) for 5 days and, when symptoms continued, was switched to famotidine (20 mg twice daily) and sucralfate (1 g four times daily). One week later he developed nausea and jaundice. He denied fever, chills, rash or pruritus. He had no history of liver disease, alcohol abuse or risk factors for viral hepatitis. He had been taking acetaminophen for the previous ten days (625 mg four times daily). On physical examination, he was jaundiced and had tenderness over the liver, but no fever, rash or signs of chronic liver disease. Laboratory results showed elevations in serum bilirubin with moderate elevations in serum ALT and alkaline phosphatase (Table). He tested negative for markers of viral hepatitis (A, B and C) and for autoimmune liver disease. Acetaminophen levels were normal (7 µg/mL: normal therapeutic range 10-20). Abdominal ultrasound showed no gallstones or evidence of biliary obstruction. Famotidine was stopped and he rapidly improved. A liver biopsy was not done. When seen five weeks later, all laboratory tests had returned to normal.

Key Points

| Medication: | Famotidine (40 mg daily) |

|---|---|

| Pattern: | Hepatocellular (R=6.1) |

| Severity: | 3+ (jaundice, hospitalization) |

| Latency: | 1 week |

| Recovery: | 5 weeks |

| Other medications: | Acetaminophen (~2.5 g daily) |

Comment

This patient developed a mild acute hepatitis 1 week after starting famotidine. While he had also been taking moderate doses of acetaminophen (2.5 g per day for 10 days), the pattern of injury was not typical of acetaminophen hepatotoxicity and acetaminophen levels were actually below the therapeutic range and well below the toxic range on admission. The pattern and course of the liver injury was quite typical of idiosyncratic drug induced liver injury and compatible with the type of injury that has been reported with H2 blockers with a short latency (1 week), a hepatocellular or mixed pattern of liver enzyme elevation and rapid recovery upon stopping. An issue is whether the 5 days of ranitidine may have caused or contributed to the injury and whether there may be cross sensitivity to hepatic injury among the various H2 blockers. Such cross sensitivity has been shown between famotidine and cimetidine (Case 2 below).

Case 2. Acute liver injury due to famotidine and recurrence due to cimetidine.

[Modified from: Hashimoto F, Davis RL, Egli D. Hepatitis following treatments with famotidine and then cimetidine. Ann Pharmacother 1994; 28: 37-9. PubMed Citation]

A 51 year old woman with symptomatic duodenal ulcer disease was treated with famotidine (40 mg daily), with subsequent improvement in epigastric pain and nausea, but with reappearance of abdominal discomfort followed by dark urine, itching and jaundice starting 3 weeks later. She denied fever or rash or history of drug allergy. She was overweight (BMI = 34.1), but had lost 2.3 kilograms in the previous week. She had no history of liver disease, alcohol abuse or risk factors for viral hepatitis. On examination, she was jaundiced and had mild hepatic tenderness but no peripheral signs of chronic liver disease. Laboratory testing showed total serum bilirubin of 5.0 (direct 4.1) mg/dL, ALT 661 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 193 U/L, with normal serum albumin and prothrombin time (Table). Tests for hepatitis A, B and C were negative as were autoantibodies. Ultrasound of the abdomen showed an echogenic liver suggestive of steatosis, but no evidence of biliary obstruction. Famotidine was stopped and omeprazole (20 mg daily) substituted. She improved rapidly and liver tests were normal or near normal five weeks later, at which point cimetidine (800 mg daily) was substituted for omeprazole. One week later she redeveloped abdominal pain and nausea. The dose of cimetidine was increased, but over the next week she developed worsening symptoms and dark urine. Laboratory testing showed rises in serum bilirubin, ALT and alkaline phosphatase similar to those after famotidine therapy and cimetidine was stopped. Repeat evaluation revealed no evidence of viral hepatitis, autoimmune liver disease or biliary obstruction. She improved and was maintained on omeprazole therapy for her acid-peptic disease. In follow up 6 weeks later, liver tests had returned to normal or near-normal levels.

Key Points

| Medication: | Famotidine (40 mg daily), cimetidine (800 to 1200 mg daily) |

|---|---|

| Pattern: | Hepatocellular (R=14) |

| Severity: | 3 (jaundice, hospitalization) |

| Latency: | 3-4 weeks for famotidine, 1-2 weeks for cimetidine |

| Recovery: | 6 weeks |

| Other medications: | Antacids, occasional acetaminophen, oral contraceptives (many years) |

Laboratory Values

| Time After Starting | Time After Stopping | ALT (U/L) | Alk P (U/L) | Bilirubin (mg/dL) | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Famotidine (40 mg/day) started | ||||

| 4 weeks | 0 | 661 | 193 | 5.0 | Famotidine stopped |

| 5 weeks | 1 | 250 | 250 | 1.5 | Symptoms resolved |

| 6 weeks | 2 | 120 | 150 | 1.0 | |

| 9 weeks | 5 | 55 | Cimetidine started | ||

| 11 [2] weeks | [0] | 590 | 180 | 4.4 | Cimetidine stopped |

| [3] weeks | [1] week | 430 | 320 | 8.2 | |

| [4] weeks | [2] weeks | 190 | 210 | 1.2 | |

| [5] weeks | [3] weeks | 90 | 180 | ||

| [7] weeks | [5] weeks | 48 | 120 | 1.0 | |

| [9] weeks | [7] weeks | 44 | 60 | ||

| Normal Values* | <35 | <150 | <1.2 | ||

* Some values estimated from Figure 1, and bilirubin levels converted from µmol to mg/dL. Weeks in parentheses represent time after starting and stopping cimetidine.

Comment

This patient appeared to develop a transient and self-limiting acute hepatitis-like injury after both famotidine and cimetidine therapy. The cross reactivity of these two agents was not suspected, based upon the lack of such cross reactivity to hepatic injury between cimetidine and ranitidine. However, in the case shown above, the recurrence was more rapid and perhaps slightly more severe with the “re-exposure” using cimetidine. Typical of H2 receptor blocker induced liver injury was the rapid recovery upon withdrawal. While liver biopsy was not done, in most such instances centrolobular necrosis with inflammation and mild cholestasis is found. This patient may have had mild underlying nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, but this is a common medical condition and unlikely played a role in the clinically apparent liver injury.

PRODUCT INFORMATION

REPRESENTATIVE TRADE NAMES

Famotidine – Generic, Pepcid®

DRUG CLASS

Antiulcer Agents

Product labeling at DailyMed, National Library of Medicine, NIH

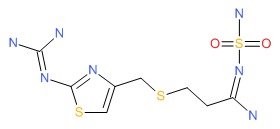

CHEMICAL FORMULA AND STRUCTURE

| DRUG | CAS REGISTRY NUMBER | MOLECULAR FORMULA | STRUCTURE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Famotidine | 76824-35-6 | C8-H15-N7-O2-S3 |

|

ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY

References updated: 25 January 2018

- Zimmerman HJ. H2 Receptors antagonists. In, Zimmerman HJ. Hepatotoxicity: the adverse effects of drugs and other chemicals on the liver. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1999, pp. 719-20.(Expert review of hepatotoxicity published in 1999 states that cimetidine and ranitidine, despite enormous use, have been implicated in a small number of cases of hepatic injury, 39 for cimetidine, 35 for ranitidine and 1 for famotidine, all cases recovering and signs of hypersensitivity being rare).

- Wallace JL, Sharkey KA. Pharmacotherapy of gastric acidity, peptic ulcers, and gastroesophageal reflux disease. In, Brunton LL, Chabner BA, Knollman BC, eds. Goodman & Gilman's the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 12th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2011, pp. 1309-22.(Textbook of pharmacology and therapeutics).

- Black M. Hepatotoxic and hepatoprotective potential of histamine (H2)-receptor antagonists. Am J Med 1987; 83: 68-75. [PubMed: 2892410](Review of hepatotoxicity of cimetidine and ranitidine and their potential role in ameliorating acetaminophen hepatotoxicity, perhaps via their inhibition of P450 activity).

- Dobrilla G, De Pretis G, Piazzi L, Boero A, Camarri E, Crespi M, Fontana G, et al. Comparison of once-daily bedtime administration of famotidine and ranitidine in the short-term treatment of duodenal ulcer. A multicenter, double-blind, controlled study. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl 1987; 134: 21-8. [PubMed: 2889255](Controlled trial comparing famotidine and ranitidine in 234 patients with duodenal ulcer disease; all had normal ALT levels at the end of therapy except for one [chronic alcoholic] patient who developed elevated aminotransferase levels on famotidine; no details given).

- Lewis JH. Hepatic effects of drugs used in the treatment of peptic ulcer disease. Am J Gastroenterol 1987; 82: 987-1003. [PubMed: 2889354](Thorough review of hepatotoxicity of antiulcer medications; 10 published cases of hepatotoxicity due to cimetidine and 12 for ranitidine, none fatal and not all convincingly due to the medication; little information available on famotidine or nizatidine).

- Saigenji K, Fukutomi H, Nakazawa S. Famotidine: postmarketing clinical experience. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl 1987; 134: 34-40. [PubMed: 2889256](Postmarketing survey of 6436 Japanese patients on famotidine found side effects in <1% and liver test elevations in 33 [<0.5%], resolving in 11 of 25 who continued therapy).

- Ament PW, Roth JD, Fox CJ. Famotidine-induced mixed hepatocellular jaundice. Ann Pharmacother 1994; 28: 40-2. [PubMed: 8123957](55 year old developed jaundice following treatment with 1 week of ranitidine and 1 week of famotidine [bilirubin 7.1 mg/dL, ALT 305 U/L, Alk P 182 U/L] with rapid resolution on stopping: Case 1).

- Hashimoto F, Davis RL, Egli D. Hepatitis following treatments with famotidine and then cimetidine. Ann Pharmacother 1994; 28: 37-9. [PubMed: 8123956](51 year old developed pain and jaundice 3-4 weeks after starting famotidine [bilirubin 5 mg/dL, ALT 661 U/L, Alk P 193 U/L], recovering rapidly on omeprazole but with recurrence 1 week after starting cimetidine [bilirubin 8 mg/dL, ALT ~590 U/L, Alk P ~320 U/L], with rapid improvement on switching again to omeprazole: Case 2).

- Howden CW, Tytgat GN. The tolerability and safety profile of famotidine. Clin Ther 1996; 18: 36-54. [PubMed: 8851452](Analysis of safety in 7483 patients in 27 trials of famotidine; side effects were uncommon [<1% for any specific symptom] and no more common than with placebo or comparator agents such as ranitidine; ALT elevations occurred in 2.2% on famotidine, 2.0% on ranitidine and 2.7% on placebo; only 1 patient discontinued famotidine because of elevation of liver tests).

- García Rodríguez LA, Ruigómez A, Jick H. A review of epidemiologic research on drug-induced acute liver injury using the general practice research data base in the United Kingdom. Pharmacotherapy 1997; 17: 721-8. [PubMed: 9250549](Combined analysis of 8 epidemiologic studies using the UK General Practice Research Database estimated incidence rates of acute liver injury to be highest for isoniazid and chlorpromazine [4 and 1.3 per 1000 users], intermediate for amoxicillin-clavulanate, cimetidine and ranitidine [2.3, 2.3 and 0.9 per 10,000], and lowest for trimethoprim/ sulfamethoxazole, omeprazole, amoxicillin and nonsteroidals [5.2, 4.3, 3.9 and 3.7 per 100,000]; famotidine not discussed).

- García Rodríguez LA, Wallander MA, Stricker BH. The risk of acute liver injury associated with cimetidine and other acid-suppressing anti-ulcer drugs. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1997; 43: 183-8. [PMC free article: PMC2042728] [PubMed: 9131951](Case control study in cohort of 100,000 users of antiulcer drugs in a UK general practice database; 33 cases of acute liver injury found, 12 on cimetidine for a relative risk [RR] of 5.5, 1 on omeprazole and 5 on ranitidine did not raise RR above baseline. Latency was <2 months in 80% of cases; most antiulcer drug cases had hepatocellular or mixed enzyme patterns [15 of 18]).

- Sohn JH, Sohn YW, Jeon YC, Han DS, Hahm JS, Choi HS, Park KN, Kee CS. Three cases of hepatitis related to the use of famotidine and ranitidine. Korean J Hepatol 1998; 4: 194-9. Not in PubMed.(Two cases of hepatotoxicity attributed to famotidine: 54 year old woman developed jaundice 6 weeks after starting famotidine [bilirubin 12 mg/dL, ALT 1520 U/L, Alk P 153], resolving within 2 months of stopping; a 45 year old man developed jaundice 6 weeks after restarting famotidine [bilirubin 14 mg/dL, ALT 58 U/L, Alk P 207 U/L], resolving within 3 months of stopping).

- Jiménez-Sáenz M, Argüelles-Arias F, Herrerías-Gutiérrez JM, Durán-Quintana JA. Acute cholestatic hepatitis in a child treated with famotidine. Am J Gastroenterol 2000; 95: 3665-6. [PubMed: 11151926](13 year old developed jaundice 75 days after stopping a 30-day course of famotidine, with bilirubin rising from 9 to 26 mg/dL, ALT 1080 to 2400 U/L, Alk P 634 U/L, recovering in 2-3 months).

- Fisher AA, Le Couteur DG. Nephrotoxicity and hepatotoxicity of histamine H2 receptor antagonists. Drug Saf 2001; 24: 39-57. [PubMed: 11219486](Review of renal and hepatic complications of H2 blocker therapy).

- Russo MW, Galanko JA, Shrestha R, Fried MW, Watkins P. Liver transplantation for acute liver failure from drug-induced liver injury in the United States. Liver Transpl 2004; 10: 1018-23. [PubMed: 15390328](Among ~50,000 liver transplants reported to UNOS between 1990 and 2002, 270 [0.5%] were done for drug-induced acute liver failure, but none were attributed to an H2 blocker or proton pump inhibitor).

- de Abajo FJ, Montero D, Madurga M, García Rodríguez LA. Acute and clinically relevant drug-induced liver injury: a population based case-control study. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2004; 58: 71-80. [PMC free article: PMC1884531] [PubMed: 15206996](Analysis of General Practice Research Database from UK on 1.6 million persons from 1994-2000 found 128 cases of drug-induced liver injury [2.4/100,000 person years]; 3 cases were attributed to cimetidine for an odds ratio of 2.0 compared to controls [n=5000] which was not statistically significant; famotidine not discussed).

- Björnsson E, Jerlstad P, Bergqvist A, Olsson R. Fulminant drug-induced hepatic failure leading to death or liver transplantation in Sweden. Scand J Gastroenterol 2005; 40: 1095-101. [PubMed: 16165719](Survey of all cases of DILI with fatal outcome from Swedish Adverse Drug Reporting system from 1966-2002: 103 cases identified as highly probable, probable or possible, one case attributed to ranitidine and one to omeprazole, none attributed to famotidine).

- Sabaté M, Ibáñez L, Pérez E, Vidal X, Buti M, Xiol X, Mas A, et al. Risk of acute liver injury associated with the use of drugs: a multicentre population survey. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007; 25: 1401-9. [PubMed: 17539979](Population based survey of 126 cases of acute liver injury due to drugs between 1993-1999 in Spain; 8 were attributed to ranitidine alone [incidence 5.1/100,000 person-years] and 5 to omeprazole alone [2.1/100,000]; famotidine not mentioned).

- Chalasani N, Fontana RJ, Bonkovsky HL, Watkins PB, Davern T, Serrano J, Yang H, Rochon J; Drug Induced Liver Injury Network (DILIN). Causes, clinical features, and outcomes from a prospective study of drug-induced liver injury in the United States. Gastroenterology 2008; 135: 1924-34. [PMC free article: PMC3654244] [PubMed: 18955056](Among 300 cases of drug induced liver disease in the US collected between 2004 and 2008, 2 were attributed to ranitidine, none to famotidine or other antiulcer medications).

- Gupta N, Patel C, Panda M. Hepatitis following famotidine: a case report. Cases J 2009; 2: 89. [PMC free article: PMC2640350] [PubMed: 19173722](47 year old man with chronic hepatitis C developed an acute rise in ALT within 3 days of laparoscopic cholecystectomy and 36 hours after starting famotidine [ALT 4755 U/L, AST 8466 U/L, bilirubin 2.5 mg/dL, INR 2.4], with rapid recovery within 10 days of stopping).

- Ferrajolo C, Capuano A, Verhamme KM, Schuemie M, Rossi F, Stricker BH, Sturkenboom MC. Drug-induced hepatic injury in children: a case/non-case study of suspected adverse drug reactions in VigiBase. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2010; 70: 721-8. [PMC free article: PMC2997312] [PubMed: 21039766](Worldwide pharmacovigilance database contained 9036 hepatic adverse drug reactions in children; no antiulcer medication was among the top 40 causes).

- Reuben A, Koch DG, Lee WM; Acute Liver Failure Study Group. Drug-induced acute liver failure: results of a U.S. multicenter, prospective study. Hepatology 2010; 52: 2065-76. [PMC free article: PMC3992250] [PubMed: 20949552](Among 1198 patients with acute liver failure enrolled in a US prospective study between 1998 and 2007, 133 were attributed to drug induced liver injury, but none were caused by antiulcer medications).

- Björnsson ES, Bergmann OM, Björnsson HK, Kvaran RB, Olafsson S. Incidence, presentation and outcomes in patients with drug-induced liver injury in the general population of Iceland. Gastroenterology 2013; 144: 1419-25. [PubMed: 23419359](In a population based study of drug induced liver injury from Iceland, 96 cases were identified over a 2 year period, but none were attributed to famotidine or other antiulcer medications).

- Hernández N, Bessone F, Sánchez A, di Pace M, Brahm J, Zapata R, A Chirino R, et al. Profile of idiosyncratic drug induced liver injury in Latin America. An analysis of published reports. Ann Hepatol 2014; 13: 231-9. [PubMed: 24552865](Systematic review of literature of drug induced liver injury in Latin American countries published from 1996 to 2012 identified 176 cases, the most commonly implicated agents being nimesulide [n=53], cyproterone [n=18], nitrofurantoin [n=17] and antituberculosis drugs [n=13]; no case was linked to famotidine or other antiulcer agent).

- Chalasani N, Bonkovsky HL, Fontana R, Lee W, Stolz A, Talwalkar J, Reddy KR, et al.; United States Drug Induced Liver Injury Network. Features and outcomes of 899 patients with drug-induced liver injury: The DILIN Prospective Study. Gastroenterology 2015; 148: 1340-52.e7. [PMC free article: PMC4446235] [PubMed: 25754159](Among 899 cases of drug induced liver injury enrolled in a US prospective study between 2004 and 2013, 6 cases were attributed to antiulcer medications, 3 to ranitidine and 3 to PPIs, but none to famotidine).

- PMCPubMed Central citations

- PubChem SubstanceRelated PubChem Substances

- PubMedLinks to PubMed

- Review Histamine Type-2 Receptor Antagonists (H2 Blockers).[LiverTox: Clinical and Researc...]Review Histamine Type-2 Receptor Antagonists (H2 Blockers).. LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury. 2012

- Review Ranitidine.[LiverTox: Clinical and Researc...]Review Ranitidine.. LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury. 2012

- Review Nizatidine.[LiverTox: Clinical and Researc...]Review Nizatidine.. LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury. 2012

- Review Cimetidine.[LiverTox: Clinical and Researc...]Review Cimetidine.. LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury. 2012

- A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical study of the histamine H2-receptor antagonist famotidine in Japanese patients with nonerosive reflux disease.[J Gastroenterol. 2008]A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical study of the histamine H2-receptor antagonist famotidine in Japanese patients with nonerosive reflux disease.Hongo M, Kinoshita Y, Haruma K. J Gastroenterol. 2008; 43(6):448-56. Epub 2008 Jul 4.

- Famotidine - LiverToxFamotidine - LiverTox

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

See more...