NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Peterson BS, Trampush J, Maglione M, et al. ADHD Diagnosis and Treatment in Children and Adolescents [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2024 Mar. (Comparative Effectiveness Review, No. 267.)

6.1. Key Question (KQ) 3 ADHD Monitoring Key Points

- Very few monitoring studies have been reported and more research is needed on how youth with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) should be monitored over time.

- Different assessment modalities may provide valid but different perspectives and more than a single assessment modality may be required for comprehensive and effective monitoring of ADHD outcomes over time.

6.2. KQ 3 ADHD Monitoring Summary of Findings

We identified a small number of studies addressing a monitoring strategy.173, 203, 255, 256, 268, 274, 466, 545, 609, 629 Results of the individual studies are shown in Appendix D, Table D.3. However, studies did not provide information on the predefined key outcomes.

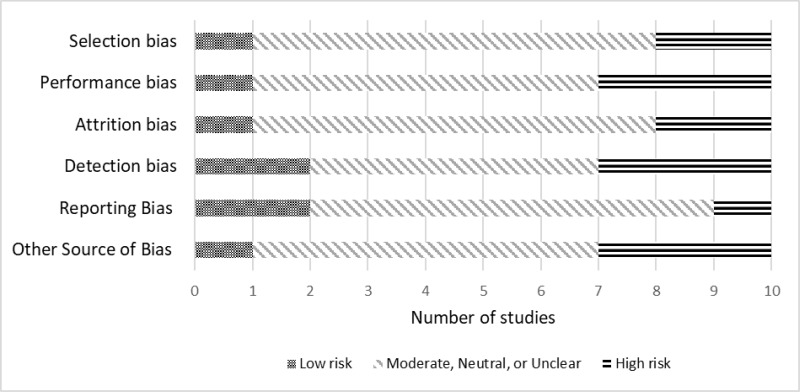

The potential for risk of bias in the KQ3 studies is documented in Figure 92. The critical appraisal for the individual studies is in Appendix D.

Across studies, selection bias was likely present in two studies.274, 466 Performance bias was present in two studies.268, 274 Attrition bias was also present in two of the identified studies.173, 203 Detection bias was determined to be present in three studies.173, 274, 466 Reporting bias was likely in one study.545 In the small set of studies, a third were rated as high risk of bias for other sources.255, 268, 629

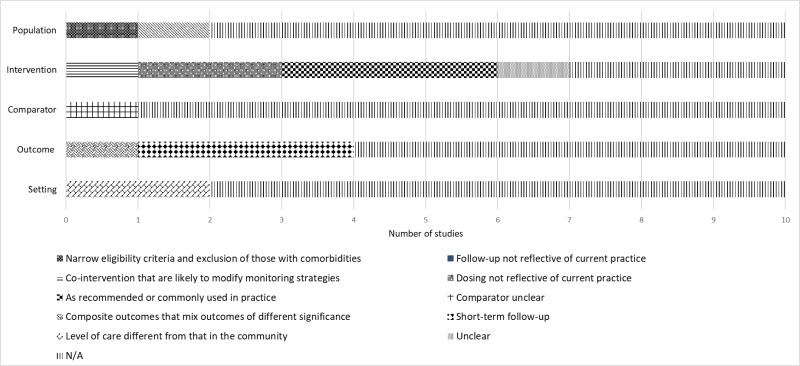

Figure 93 shows the distribution of applicability issues in KQ3 studies. The applicability for the individual studies is in Appendix D.

Given the small number of available studies, results of the different monitoring strategies are documented in Table 26. More details can be found in Appendix Table C.3.

We identified 10 studies addressing some type of monitoring strategy for ADHD.173, 203, 255, 256, 268, 274, 466, 545, 609, 629 Three studies of ADHD rating scales and/or a computerized continuous performance task assessed their reliability and sensitivity to detect symptom change over time. The studies reported a relatively poor correlation between these measures over time, whether the correlations were between different raters on the same rating scale545 or between assessment modalities (e.g., rating scale vs computerized performance test).173, 203 Both subjective assessment modalities (e.g., self-report, parent, teacher, and clinician rating scales)173, 203, 545 and more objective measurement modalities (e.g., continuous performance task)173 may be sensitive to clinical change in response to treatment, but one study suggested that subjective measures may be more sensitive to detecting treatment-associated changes in ADHD symptom severity and other functional outcomes.203

Three studies assessed the impact on ADHD symptoms of interventions that target medication prescriber training to improve either symptom monitoring or adherence to treatment guidelines. One study assessed the impact of collaborative consultative services,256 and two assessed the impact of a quality improvement intervention on outcome monitoring268, 710 or ADHD symptoms.710 Collectively, the studies showed that medication prescribers (mostly pediatricians) exhibited poor compliance in attending training programs for quality improvement in treating ADHD.256, 268 Even when they did participate in those traininigs, pediatrician compliance with treatment guidelines was poor, as the pediatricians rarely acquired ratings of symptom severity from either parents or, even less often, from teachers,256, 268 even when the intervention increased the collection of ratings compared with waitlist controls.268 Moreover, pediatricians often did not prescribe stimulant medication for youth who met diagnostic criteria for ADHD,255, 256 and when they did prescribe, the doses were sub-optimal,255 even when provided intensive advice and support services from mental health specialists.256 Youth whose prescribers participated in the consultative services from specialists, however, had greater reductions in ADHD symptom severity.256 One study assessed the validity of alerts generated by a computer algorithm based on ratings from monthly monitoring of ADHD symptom severity. Alerts were then sent to prescribers notifying them of putatively actionable clinical events.466 Prescribers deemed the alerts to be generally valid, suggesting that computerized algorithms applied to symptom ratings combined with automated clinican alerts may have clinical utility.

One study of youth who had stimulant-induced weight loss compared the effects of (1) height and weight monitoring alone, with (2) caloric supplementation plus monitoring, and (3) medication holidays plus monitoring on the trajectory of weight gain.274 All three interventions increased weight significantly, suggesting that monitoring of height and weight during medication administration may be efficacious in attenuating stimulant-induced weight loss, though the study did not include the no-intervention control that would have been needed to prove this. Intent-to-treat analyses showed that the addition of caloric supplementation or medication holidays did not provide significant incremental benefit on attenuating weight loss when compared with monitoring alone, though per-protocol analyses suggested that the use of these additional interventions yielded significant additional benefits.

One study used a mobile app to allow patients or their parents to continuously report their clinical status. The study only reported on eight weeks of follow up after initiating the intervention.609 One study continuously assessed patients and evaluated the use of an electronic bottle cap for stimulant medication to monitor treatment adherence.629 Non-adherence was shown to be higher when monitored with this bottle cap compared with patient report, clinician rating, and pill count. The methods used to assess adherence correlated weakly with one another. Non-adherent patients had more severe symptoms at baseline and inferior improvement compared with adherent patients, providing evidence for the validity of the bottle cap method for monitoring adherence. If the bottle cap is considered the gold-standard, then self-reports, clinician impressions, and even pill counts would be deemed unreliable measures of medication adherence.

Figures

Figure 92Risk of bias in Key Question 3 ADHD monitoring studies

Notes: ADHD = attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

Tables

Table 26KQ3 monitoring strategies evidence

|

Study: Author, Year; Location |

Intervention, Analysis, Follow Up | Results |

|---|---|---|

|

Cedergren, 2021173 Sweden |

Open-label monitoring consisting of 5 follow-up visits in 12 months using a continuous performance test (QbTest) and investigator rating on the ADHD-RS. Qualitative comparison of change in ADHD-RS and QbTest scores over 12 months Naturalistic follow up, with medication administered according to clinician judgement of need. |

Bonferroni-adjusted pairwise comparisons showed statistically significant reductions in QbTest and ADHD-RS scores over the 12-month study. Both measures appear to capture symptom change over time, but weak correlations between the measures suggest that their role in medical follow-up might be complementary rather than interchangeable. |

|

Cohen, 1989203 United States |

Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study of the use of monitoring ADHD symptoms – before and during treatment with methylphenidate – using the ADD-H Comprehensive Teacher Rating Scale, Conners parent rating scale, and the Gordon Diagnostic System (a computerized continuous performance task assessing vigilance and impulse control). Group differences in change in symptom scores over time. Naturalistic follow up, before and during treatment with fixed-dose (5mg for children weighing less than 30kg, 10mg for children weighing 30kg or more), short-acting methylphenidate administered twice daily for 1 month, with measures collected at baseline, 1 month (the time of crossover), and 2 months (endpoint). |

Both rating scales demonstrated significant change in symptoms (inattention and hyperactivity on the ADD-H scale; hyperactivity on the Conners scale) during treatment with methylphenidate compared with placebo, whereas the Gordon task did not demonstrate change. Rating scales, but not this continuous performance task, appear helpful in monitoring the short-term effects of stimulant treatment. |

|

Epstein, 2007256 United States |

12 pediatric practices were randomly assigned to receive access to collaborative consultative services or a control group. In the collaborative consultation services, pediatricians were encouraged and assisted to use rating scales for symptom monitoring and titration trials to determine optimal medication dosages. Physicians were taught to prescribe 4 different doses of methylphenidate during a titration trial (placebo, 18 mg, 36 mg, 54 mg); the order of week-long dosing was blinded but standardized across patients (week 1, 18 mg; week 2, placebo; week 3, 36 mg; week 4, 54 mg) to determine optimal dosing for each patient. Parents and teachers completed weekly behavioral ratings (Conners Global Index) & side effect rating scales. Data were returned to Duke Univ psychiatrist to determine the best starting medication dose; a report describing the titration results was faxed back to pediatricians. Patients in control group practices received treatment as usual, without access to consultative services. Assessed Conners Global Index & side effect rating scales. Monthly follow up with Conners and side effect rating scales for 12 months, sent to Duke U psychiatrists for interpretatin, with recommendations returned to the pediatrician | Use of symptom ratings did not differ significantly by group, nor did the change in symptoms over time. Pediatrician compliance with the collaborative consultation service was poor (pediatricians for 29 of 59 patients in the consultation group received a titration trial and 13/59 participated in monthly medication monitoring). Preliminary secondary analyses indicated that those children whose pediatricians complied with titration had significantly better outcomes compared with those who did not and TAU controls (group × time P<.01) Children in the collaborative consultation service–complier group had a 27% reduction in symptom scores compared with 18% reduction in the TAU controls and 13% reduction in consultation non-compliers. |

|

Epstein, 2016255 United States |

Cluster randomized controlled trial of either a technology-assisted quality improvement (QI) intervention or TAU control. QI intervention consisted of 4 training sessions, office flow modification, guided QI, and an ADHD Internet portal to assist with treatment monitoring versus TAU control practices Assessed intervention effects on parent- and teacher-rated ADHD severity using on the Vanderbilt ADHD total symptom score. 12 months follow up | Intent-to-treat analyses examining outcomes (parent ratings of ADHD severity) in all 577 children assessed for ADHD were not significant (b=−1.97, P=0.08), but among the 373 children prescribed ADHD medication, a significant intervention effect on reducing parent-rated symptom severity (b=−2.42, P=0.04) but not teacher-rated symptoms was observed. Prescriber compliance with treatment guidelines was poor, as only 373 of the 577 patients received medication at any time in the 1-year follow-up, and many who did receive it were prescribed sub-optimal doses. Compared with the usual care group, providers in the intervention group had 25% more patient contacts (d=.38, p=.0008) and collected 4.6 (d=.57, p<.0001) and 9.9 (d=.54, p<.0001) times more parent and teacher ratings, respectively. However, providers in the intervention group collected parent ratings in only half and teacher ratings in a quarter of their patients during the initial year of medication treatment. |

|

Fiks, 2017268 United States |

Cluster-randomized open label trial at the practice level (9 intervention, 10 control sites) for 3-component quality-improvement program that employs distance learning: (1) 3 15-minute Web-based presentations on evidence-based practices for managing ADHD in primary care; (2) optional collaborative consultation with ADHD experts via a health system online networking site or private email/telephone conversation; (3) and performance feedback reports or calls every 2 months informing them of their rates of sending and receiving ADHD rating scales from parents and teachers and allowed them to compare their results to results of the entire group; feedback reports were discussed during four, 1-hour conference calls). Participation qualified for Maintenance of Certification credit from the American Board of Pediatrics. Collection of rating scales was facilitated via an electronic application linked to the electronic health record versus waitlist control Number of parent and teacher rating scales sent out and received back assessed | Differences between intervention arms were not statistically significant, though clinicians in both study arms were significantly more likely to administer and receive parent and teacher rating scales compared to an 8-month baseline period. Intervention clinicians who participated in at least one performance feedback call were more likely to send out parent rating scales than intervention clinicians who did not participate (relative difference of 14.2 percentage points, 95% CI: 0.6, 27.7. For all study outcomes, practices with the highest rates of clinician participation in the study (≥ 80%), were not superior to practices with lower rates of involvement (< 80%). Participation was low (105 of 166 invited); 42 of 53 in the intervention group completed all 3 education presentations; 30 (57%) participated in at least one feedback call, and 19 (36%) participated in all 3 components of the intervention. |

|

Florida International University, 2010274 United States |

Randomized to receive either osmotic release oral system-methylphenidate alone (78%) or behavioral therapy alone (22%). After 6 months, children with a decline in body mass index >0.5 z-units were randomized to 1 of 3 weight recovery treatments: (1) monthly height/weight monitoring plus daily medication; (2) drug holidays on non-school days (with monthly monitoring); or (3) daily caloric supplements (with daily medication and monthly monitoring). Standardized body weight and height assessed 18 follow-up visits over 30 months | All groups significantly increased their weight gain. Drug holidays + monitoring, caloric supplementation + monitoring, and monitoring alone all led to increased weight velocity in children taking CNS stimulants, but with no differences between groups, and no intervention led to increased height velocity. When analyzed by what parents did (versus what they were assigned to), caloric supplementation (p<0.01) and drug holidays (p<0.05) increased weight velocity more than monitoring of height and weight. Over the entire study, participants declined in standardized weight (−0.44 z-units) and height (−0.20 z-units). |

|

Oppenheimer, 2019466 United States |

Naturalistic study of a Web-based platform enabling clinicians to administer online monthly clinical questionnaires to parents and teachers for monitoring of patients remotely between visits. Trigger algorithm alerts clinicians to clinically actionable events that are documented in the medical record versus non-alert group Patients were the unit of analysis. Parent and teacher reports of current medication, medication side effects inventory, Vanderbilt ADHD Parent Rating Scale, Clinical Global Impression-Severity (CGI-S) scale, and Clinical Global Impression-Improvement (CGI-I) scale 15 months follow up | Trigger algorithms produced alerts requiring immediate review in 8% of the parent reports. Clinicians perceived 74% of alerts to be significant enough to prompt urgent follow-up with parents, suggesting a low rate of false positive alerts. Patients who generated alerts compared to those who did not had more severe ADHD symptoms (beta = 5.8, 95% CI: 3.5–8.1 [p < 0.001] in the 90 days prior to an alert, further supporting validity of the alerts. |

|

Smith, 2000545 United States |

A assessed the reliability, validity, and unique contributions of self-reports by adolescents receiving treatment for ADHD in a summer treatment program that included self-monitoring as a treatment component. Self-reported IOWA Conners Inattention/Overactivity and Oppositional/Defiant subscales, ratings of interactions with peers and staff. Assessed changes in reliability during a placebo-controlled, cross-over study of 30 mg of methylphenidate. Observed frequencies of negative behavior, rating from parents and teachers | Average reliability for the adolescent self-report across all measures was .78 (range .74-.83), similar to the reliability of .82 for counselors (range .78-.85), and significantly better than the teacher reliability of .60 (range .51-.68). Teacher and counselor ratings on the Conners changed significantly during stimulant treatment whereas adolescent self-ratings did not. The findings suggest that adolescents can provide reliable information on their symptoms, but not beyond what parents can provide. Adolescents may also be poor sources of information about the change in ADHD symptoms, but a good source of intormation about improved interactions with others in response to treatment. |

|

Weisman, 2018609 Israel |

Mobile app allows patients or their parents to report their clinical status following initiation of prescription or after changing medication dosage; purpose of the app is to facilitate communication with MD; app includes questions on severity of ADHD symptoms and potential side effects and can also function as a medication reminder Treatment as usual, without app |

CGI-Severity no significant difference No significant difference on ADHD-RS, possibly due to inadequate power, Significant difference (p= 0 .008) favoring intervention group on the Clinician Rating Scale (CRS). Intervention group had significantly better adherence, as measured by pill count (p < .015). |

|

Yang, 2012629 Korea |

Naturalistic study of symptom monitoring and medication adherence assessed using the Medication Event Monitoring System, a bottle cap with a microprocessor that records all instances and times that the bottle is opened Patient self-report, clinician rating, pill count assessed; measure of adherence 8 weeks follow up | The rate of non-adherence was 46.2%, higher than patient self-report of 17.9%, clinician rating of 31.7%, and pill count of 12.8%. Pill count and monitoring system concordance was 0.249 (95% CI: 0.102-0.386). Self-report concordance was 0.237 (95% CI: −0.024-0.468). Non-adherent patients had more severe symptoms at baseline and inferior improvement compared with adherent patients. |

Notes: ADD-H = attention deficit disorder with hyperactivity, ADHD = attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, ADHD-RS = ADH rating scale, CI = 95% confidence interval, CGI-I = Clinical Global Impression-Improvement scale, CNS = central nervous system stimulants, CRS = clinician rating scale, GGI-S = (Clinical Global Impression-Severity scale, KQ = Key Question, MD = medical doctor, QB test = quantified behavioral test, RR = relative risk, TAU = treatment as usual