NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Committee for Assessing Progress on Implementing the Recommendations of the Institute of Medicine Report The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health ; Institute of Medicine; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Altman SH, Butler AS, Shern L, editors. Assessing Progress on the Institute of Medicine Report The Future of Nursing. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2016 Feb 22.

Assessing Progress on the Institute of Medicine Report The Future of Nursing.

Show detailsRacial and ethnic minorities, notably African Americans and Hispanics/ Latinos, are presently underrepresented in the nursing workforce, as well as in many health occupations. The Future of Nursing identifies this lack of diversity as a challenge for the nursing profession and states that a more diverse workforce will help better meet current and future health care needs and provide more culturally relevant care (IOM, 2011). The report notes that the most effective way to achieve workforce diversity is to increase diversity in the pipeline of students pursuing nursing education. The report does not offer any stand-alone recommendations addressing diversity, but it does include improving and increasing diversity in recommendations 4, 5, and 6 with reference to baccalaureate and doctoral education as well as lifelong learning (see Chapter 3). And one of the pillars of the Future of Nursing: Campaign for Action (the Campaign) is “promoting diversity” (CCNA, n.d.-a).1

INTRODUCTION

The lack of racial and ethnic diversity is a significant issue across the health care workforce that has been documented for decades. Present data show the current status of diversity in nursing and other health professions (HRSA, 2006, 2015a; IOM, 2004; NCSL, 2014; OMH, 2011; Sullivan Commission on Diversity in the Healthcare Workforce, 2004) (see Table 4-1).

TABLE 4-1

U.S. Health Occupations by Race, Ethnicity, and Sex, 2010-2012.

As indicated in Table 4-1, the nursing workforce is more diverse than many of the other health professions requiring advanced education. It also is worth noting that diversity is greatest among licensed practical nurses (LPNs)/licensed vocational nurses (LVNs); nursing, psychiatric, and home health aides; and medical assistants and other health support occupations. As the Sullivan Commission (2004) report notes, “minority students lag behind white students at every educational level, trailing in nearly all key scholastic indicators, such as . . . high school completion rates, college enrollment rates, and graduation rates. The gap between the primary and secondary educational experience of whites versus that of Hispanics, African Americans, Native Americans, and some Asian subgroups is wide, deep, and persistent” (p. 73). That report also observes that “underrepresented minority students come disproportionately from families with lower income and lower wealth than whites and are more likely to perceive the cost of an education as a deterrent or an unmanageable burden” (p. 92). A 2002 report by the Advisory Committee on Student Financial Assistance states that 48 percent of qualified low-income students forgo 4-year colleges and universities because of the financial burden (Advisory Committee on Student Financial Assistance, 2002). A 2013 presentation of the Advisory Committee noted that inequalities in access to college were worsening (Advisory Committee on Student Financial Assistance, 2013).

ACTIVITY

Nationwide, many stakeholder organizations in health care, education, and government have taken steps to increase the diversity of the nursing workforce and of the health professions more broadly. For example, the Sullivan Alliance to Transform the Health Professions was established in 2005 to advance the recommendations of two important reports released in 2004: the Sullivan Commission report cited above and the Institute of Medicine (IOM) report In the Nation's Compelling Interest: Ensuring Diversity in the Health-Care Workforce (IOM, 2004). The Sullivan Alliance became a 501(c)3 nonprofit organization in 2011. Six state alliances were established between 2004 and 2015. These alliances operate as “‘pathfinders' to identify and test best practices to diversify the health workforce” by developing collaborations between educational institutions at both the community college and the university level and health centers (The Sullivan Alliance, 2015).

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) has been committed to addressing workforce diversity, stating that “national and local strategic plans encompass required elements to attend to attracting, maintaining, and advancing personnel with diverse characteristics” (VA, 2015a, p. 22). The VHA has used workforce databases to track personnel characteristics and ensure the diversity of advisory groups and committees. The VHA's Nursing Innovation Award was launched in 2003. The following year, the theme of the award was “Enhancing the Diversity of the [U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA)] Nursing Workforce and/or Addressing Culturally Sensitive Patient Care,” and 10 nurse-led interdisciplinary teams received awards for their contributions in these areas (VA, 2015a,b).

In the U.S. Department of Defense, the Tri-Service Nurse Corps has achieved greater success than the nation as a whole in recruiting and educating a nurse workforce that is more diverse in both gender and race/ethnicity than the civilian nurse workforce. Men represent 36.9 percent of nurses in the Army Nurse Corps, 36.0 percent in the Navy Nurse Corp, and 29.2 percent in the Air Force Nurse Corps.2 Non-Hispanic whites make up 62 percent of nurses in the Army, 62.5 percent of nurses in the Navy, and 71.5 percent of nurses in the Air Force Nurse Corps.3 The proportion of nurses in the military who are Hispanic or Latino is similar to that in the civilian workforce, but it is lower than the proportion in the U.S. population. A variety of financial incentive programs for the pursuit of nursing, including loan repayment programs for nurses already trained and financial support for ongoing nursing education, may help break down barriers to greater diversity in the military nursing workforce (Donelan et al., 2014; U.S. Army, n.d.). The workforce is recruited in part from enlisted personnel who already serve in health care roles and through new partnerships with colleges and universities that are located near major U.S. military bases. Recent research documenting factors driving career interest in these populations has helped to shape further recruitment efforts (Donelan et al., 2014).

As noted above, the Campaign has made promoting diversity one of its pillars (CCNA, n.d.-a), noting that “Action Coalitions should look at their state's demographics to determine what aspects of identity need to be addressed in regards to diversity and meeting the population's health care needs” (CCNA, n.d.-b). To support this pillar, the Campaign convenes a Diversity Steering Committee composed of representatives from the American Assembly for Men in Nursing, Asian American/Pacific Islander Nurses Association, National Alaska Native American Indian Nurses Association, National Association of Hispanic Nurses, National Black Nurses Association, National Coalition of Ethnic Minority Nurse Associations, and Philippine Nurses Association of America (CCNA, n.d.-d).

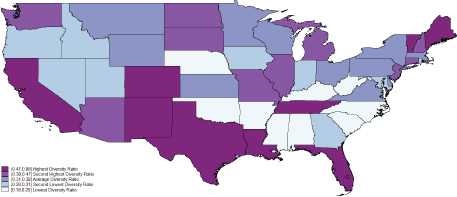

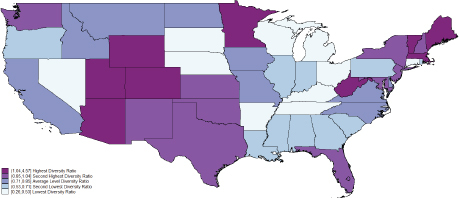

A 2013 survey of the Action Coalitions illustrates the degree of self-reported focus on racial/ethnic diversity in nursing. Among the survey respondents, 8 states and the District of Columbia said they considered this issue a high priority, while 18 states said they considered it a low priority (TCC Group, 2013) (see Figure 4-1). In the same survey, only 32 percent of respondents said they felt that the diversity of the nurse workforce had improved (TCC Group, 2013). Most state Action Coalitions said they did not consider diversity a “main focus” of their work (see Figure 4-2).

FIGURE 4-1

Level of focus on diversity among state Action Coalitions. NOTE: This map is based on aggregated responses from states about their Action Coalition's focus on racial/ethnic and gender diversity in nursing. State scores were divided into high, medium, and (more...)

FIGURE 4-2

State Action Coalition members' focus on areas of diversity identified by The Future of Nursing and the Campaign. NOTES: Data are based on responses of 1,100 survey respondents from 49 state Action Coalitions, including the District of Columbia. Scores (more...)

After this survey was conducted, the Campaign began requiring—not just recommending—that states receiving State Implementation Program (SIP) funding have a diversity action plan in place. This requirement evolved from a preference in the first SIP request for proposals (RFP), issued in 2011. At that time, the Campaign noted that “preference will be given to [Action Coalitions] that include a plan for advancing diversity as part of their recommendation implementation” (CCNA, 2011), whereas the most recent RFP states that “all proposals must address the goal of increasing the diversity of the nursing workforce, faculty, and leadership to meet the state population's health care needs. Preference will be given to [Action Coalition] applications that describe robust and achievable mechanisms to enhance diversity and inclusive practices” (CCNA, 2014). Grantees of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation's (RWJF's) Academic Progression in Nursing program (see Chapter 3) also are required to have diversity action plans.4

According to the Campaign, as of May 2015, 41 state Action Coalitions were working on developing and/or implementing diversity action plans, while 21 Action Coalitions had an approved diversity action plan (CCNA, 2015a). The Campaign's Diversity Steering Committee has developed criteria for effective diversity action plans (Villarruel et al., 2015, p. 59):

- Strategies should be developed at the right “line of sight” (focusing not only on process but on outcomes), targeted to the state level, and grounded in the IOM recommendations. The committee encourages Action Coalitions to focus on their states' population and demographic needs.

- Efforts should be data based and data driven. The committee recommends that an Action Coalition's plans begin by determining baseline data regarding the state's population and workforce.

- Choice of focus, direction, and strategies should be evidence based. The committee encourages Action Coalitions to use lessons learned from other state-level coalitions, institutions, and minority organizations that implemented successful programs aimed at increasing diversity.

- The emphasis should be on sustainability and a credible infrastructure for continuous work. The committee wants to ensure that efforts can be sustained over time, and that plans can be replicated or adopted by other organizations or states.

- Diversity should be thoroughly embraced by each Action Coalition. The committee wants to ensure that the coalitions are addressing the diversity of their leadership as well as using diversity strategies with regard to education progression, removing barriers to practice and care, interprofessional collaboration, and data collection initiatives.

In addition, the Campaign sends diversity consultants to states to provide assistance, convenes an Increasing Diversity through Data Learning Collaborative for state Action Coalitions, and compiles resources relating to diversity on the Campaign website (CCNA, 2015a, n.d.-c).

Because The Future of Nursing does not include a stand-alone recommendation or key message relating to diversity, and because diversity is an issue that cuts across education, practice, and leadership, the Campaign does not have a primary dashboard indicator relating to diversity. However, it does track the following supplemental indicators that relate to the diversity of the nursing workforce and the workforce pipeline (CCNA, 2015b):

- racial and ethnic composition of the registered nurse (RN) workforce in the United States;

- new RN graduates by degree type, by race/ethnicity;

- new RN graduates by degree type, by gender;

- diversity of nursing doctoral graduates by race/ethnicity; and

- diversity of nursing doctoral graduates by gender.

The Campaign also tracks whether states are collecting race and ethnicity data on their nursing workforce. As noted in Chapter 6, the Campaign dashboard shows that as of 2013 most, but not all, states were collecting these data. Doing so could help states create benchmarks for workforce diversity and measure progress as diversity initiatives are implemented.

PROGRESS

Increasing the diversity of the overall nurse workforce is inevitably a slow process because only a small percentage of the workforce leaves and enters each year, whereas the pipeline can change more rapidly, as most degree programs cycle in 2 to 4 years. Thus, the pipeline will respond more quickly to efforts to increase diversity relative to the pool of all nurses; the pipeline also represents the future workforce. Changing the makeup of the pipeline depends, of course, on increasing diversity among those who apply to, are accepted to, enroll in, and graduate from nursing degree programs.

In the United States, according to the most recent data available to the committee, African Americans made up 13.6 percent of the general population aged 20 to 40 in 2011-2013,5 but 10.7 percent of the RN workforce, 10.3 percent of 2011-2013 associate's degree graduates, and 9.3 percent of 2011-2013 baccalaureate graduates. The disparity is even wider for Hispanics/Latinos, who made up 20.3 percent of the general population aged 20 to 40 in 2011-2013,6 but only 5.6 percent of the RN workforce, 8.8 percent of 2011-2013 associate's degree graduates, and 7.0 percent of 2011-2013 baccalaureate graduates. Men made up 9.2 percent of the RN workforce (see Table 4-1), 11.7 percent of baccalaureate nursing students, and 11.6 percent of baccalaureate nursing graduates in the 2013-2014 academic year.7

Trends in the Diversity of the Nursing Workforce

Only 5 years after the release of The Future of Nursing, it is still too soon to see significant changes in the diversity of the national nursing workforce that may be attributable to the recommendations of the report or the activities of the Campaign. To examine trends in the diversity of the nursing workforce, the present committee considered data over a period of time that includes but also predates the Campaign.

Gender Diversity

Changing career options for women and men have resulted in more gender diversity in many health care occupations in the United States. The proportion of nurses who are males remains below 10 percent of the nurse workforce, but it increased incrementally from 2.7 percent in 1970 to 9.6 percent in 2011 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2013). By contrast, in 1970, 7.6 percent of physicians were women, and by 2012 that proportion had risen to 35 percent (HRSA, 2015a; More and Greer, 2000). Gender diversity is greatest in advanced practice nursing. Nine percent of nurse practitioners (NPs) are male, compared with 41 percent of certified registered nurse anesthetists (CRNAs) (U.S. Census Bureau, 2013). Data from the 2011 American Community Survey (ACS) show that males nurses earn more than their female counterparts in several categories, including RNs, NPs, and CRNAs.

Racial and Ethnic Diversity

An analysis of the ACS from 2001 to 2013 indicates that racial and ethnic diversity in the nursing workforce has been increasing: over this period, the number of active Hispanic/Latino nurses doubled, and the number of African American nurses rose by 70 percent (see Table 4-2). Yet despite steady gains in the number of racial and ethnic minority nurses and advances in the proportion of nurses who are minorities, the diversity of the nursing workforce still is not representative of the diversity of the general U.S. population.

TABLE 4-2

Number and Percentage of Active Registered Nurses (RNs) Who Are African American and Hispanic/Latino.

According to a 2015 report of the American Nurses Association (ANA) (McMenamin, 2015), the youngest generation of nurses is more diverse than the oldest: 80.7 percent of nurses over age 60 are white non-Hispanic, compared with 71.6 percent of nurses under 40. The report suggests that as older nurses retire, workforce diversity will improve; however, this analysis does not take into account the proportion of minority nurses in the pipeline.

Trends in the Diversity of the Pipeline

Associate's and Baccalaureate Degrees in Nursing

The number and proportion of enrollees in and graduates from baccalaureate nursing programs who are male increased between 2005 and 2014. Male enrollees in baccalaureate programs increased from 15,705 (9.7 percent) in 2005, to 27,200 (11.4 percent) in 2010, to 37,410 (11.7 percent) in 2014.8 Male graduates in baccalaureate nursing programs increased from 3,752 (9.1 percent) in 2005, to 8,046 (10.9 percent) in 2010, to 12,952 (11.6 percent) in 2014. These increases suggest that the number and proportion of males in the nursing workforce will likely continue to rise gradually. Likewise, the number of African American and Hispanic/Latino nursing graduates in both associate's and baccalaureate programs increased steadily from 2004 to 2014, consistent with the pace observed in the general nursing workforce.

The representation of minorities in the population of nursing students and graduates reveals some differences between Hispanics/Latinos and African Americans. The number of Hispanic/Latino nursing graduates rose steadily in both associate's and baccalaureate programs from 2004 to 2013, and the proportion of Hispanics/Latinos increased from 6.4 percent to 8.8 percent of associate's graduates and from 5.9 percent to 7.0 percent of baccalaureate graduates (see Figure 4-3). Despite these increases, however, the percentage of Hispanic/Latino graduates lags behind the percentage of Hispanics or Latinos in the general population aged 20 to 40 in 2013 (20.3 percent9). The number of African American graduates also increased over this period, but the proportion of African American nursing students and graduates remained essentially unchanged (see Figure 4-4). The percentages of African American graduates in 2013—10.3 percent for associate's degrees and 9.3 percent for baccalaureate degrees—are below the percentage of the general population aged 20 to 40 that is African American (13.6 percent10).

FIGURE 4-3

Number and percentage of Hispanic/Latino associate's degree and entry-level baccalaureate graduates, 2004-2014. a SOURCE: The Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), U.S. Department of Education; (more...)

FIGURE 4-4

Number and percentage of African American associate's degree and entry-level baccalaureate graduates, 2004-2014. a SOURCE: The Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), U.S. Department of Education, (more...)

Baccalaureate Completion Programs

The past several years have seen a significant increase in the number of nurses with an associate's degree or diploma who have returned to school to obtain a baccalaureate degree. According to American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) data, the number of Hispanic/Latino nurses graduating from baccalaureate completion programs also increased significantly, from 532 in 2004 to 2,220 in 2013. Hispanics/Latinos represent 6.3 percent of baccalaureate completion graduates in 2013, slightly lower than their proportion in entry-level baccalaureate programs (7 percent). The number of African Americans graduating from baccalaureate completion programs increased from 1,265 in 2004 to 5,151 in 2013. In 2013, African Americans represented 14.5 percent of baccalaureate completion graduates, compared with 9.3 percent of entry-level baccalaureate graduates, a striking difference that warrants further investigation (see Table 4-3).

TABLE 4-3

Number and Percentage of African American and Hispanic/Latino Baccalaureate Completion Graduates, 2004-2013.

Master's and Doctoral Programs

AACN data show that the numbers of African American and Hispanic/Latino enrollees in master's programs both more than tripled between 2005 and 2014. African American enrollees increased from 4,468 in 2005 to 14,911 in 2014, and Hispanic/Latino enrollees increased from 1,953 to 6,575 (see Figure 4-5). The proportion of all master's students that are African American increased from 10.7 percent to 14.7 percent, and that of Hispanic or Latino students increased from 4.7 percent to 6.5 percent (see Figure 4-5). The number of minority students enrolled in research-focused doctorate programs increased from 582 in 2005 to 1,339 in 2014 (see Figure 4-6).

FIGURE 4-5

Numbers and percentages of racial and ethnic minority enrollees in nursing master's degree programs, 2005-2014. SOURCE: Data received from AACN, August 28, 2015.

FIGURE 4-6

Numbers and percentages of racial and ethnic minority enrollees in research-focused nursing doctoral programs, 2005-2014. SOURCE: Data received from AACN, August 28, 2015.

State-by-State Variation in the Diversity of the RN Pipeline

While the percentage of minorities in nursing has been trending upward nationwide, there is a significant amount of variation at the state level with regard to the diversity of the nursing pipeline relative to the state population aged 20-40—the general age of nursing graduates (see Figures 4-7 through 4-10). It is important to compare the nursing pipeline and the general population at the state level to inform state policy and planning around educational and practice diversity issues.

FIGURE 4-7

State-level diversity in African American graduates of associate's degree programs. NOTE: An index showing the relative representation among nursing graduates is calculated by dividing the percentage of African American graduates by the percentage of (more...)

FIGURE 4-10

State-level diversity in Hispanic/Latino graduates of baccalaureate nursing programs. NOTE: An index showing the relative representation among nursing graduates is calculated by dividing the percentage of Hispanic/Latino graduates by the percentage of (more...)

FIGURE 4-8State-level diversity in Hispanic/Latino graduates of associate's degree programs

NOTE: An index showing the relative representation among nursing graduates is calculated by dividing the percentage of Hispanic/Latino graduates by the percentage of Hispanics/ Latinos in the population of the state aged 20-40, the general age of nursing graduates.

SOURCES: The Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), U.S. Department of Education, 2011-2013, for the percentage of graduates by race and ethnicity; American Community Survey, U.S. Census Bureau, for the percentage of the population aged 20 to 40 by race/ethnicity. Calculation of the state diversity index by the George Washington University Health Workforce Institute.

FIGURE 4-9State-level diversity in African American graduates of baccalaureate nursing programs

NOTE: An index showing the relative representation among nursing graduates is calculated by dividing the percentage of African American graduates by the percentage of African Americans in the population of the state aged 20-40, the general age of nursing graduates.

SOURCES: The Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), U.S. Department of Education, 2011-2013, for the percentage of graduates by race and ethnicity; American Community Survey, U.S. Census Bureau, for the percentage of the population aged 20 to 40 by race/ethnicity. Calculation of the state diversity index by the George Washington University Health Workforce Institute.

Faculty

In a 2015 fact sheet, AACN notes that “the need to attract diverse nursing students is paralleled by the need to recruit more faculty from minority populations. Few nurses from racial/ethnic minority groups with advanced nursing degrees pursue faculty careers” (AACN, 2015). Data from AACN's 2015 annual survey show that faculty in baccalaureate or higher-level programs are less diverse than both the nurse workforce overall and the enrollees and graduates of nursing degree programs (see Table 4-4). Among all full-time nursing school faculty, 7.1 percent are African American, and 2.3 percent are Hispanic/Latino; 5.7 percent are male.11

TABLE 4-4

Numbers and Percentages of Full-Time Nurse Faculty by Race/Ethnicity, 2005, 2010, and 2014.

Funding

While initiatives to increase the diversity of the nursing workforce remain as important as ever, if not more so, critical funding sources for such initiatives have remained relatively flat. In fiscal year (FY) 2015, approximately $15 million was appropriated for the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) Title VIII Nursing Workforce Diversity program, which promotes diversity by engaging and recruiting underrepresented individuals into nursing and providing them with resources that assist with their retention and advancement in educational programs. HRSA's FY2016 appropriations justification includes a request for $14 million for a new program, the Health Workforce Diversity Program, which would focus on education, training, and practice issues for individuals from disadvantaged backgrounds. HRSA's Health Careers Opportunity Program, although proposed twice for elimination, has remained funded at slightly below $15 million per year since FY2012, a sharp decline from FY2009 ($19.13 million + $2.51 million from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act [ARRA]) (HRSA, 2012, 2015b).

DISCUSSION

A more diverse nursing workforce is needed to provide culturally relevant care to an increasingly diverse population. Evidence suggests that racially, ethnically, and socioeconomically diverse health care providers are likely to practice in communities with similar populations, improving access to and quality of health care in those communities (HRSA, 2006; IOM, 2004, 2011). To be successful, an effort to improve the diversity of the nursing workforce must focus on each step along the professional pathway, from recruitment, to educational programs, to retention and success within those programs, to graduation and placement in a job, to retention and advancement within a nursing career. Recruitment of diverse populations, in particular, could help improve the diversity profile of the profession. As seen in Table 4-1, a significant proportion of non-RNs who are working in health care—LPNs/LVNs and nursing, psychiatric, and home health aides—are minorities. For example, African Americans represent 10.7 percent of RNs, but 25 percent of LPNs/LVNs and 37.5 percent of health aides. This diverse pool of health care professionals could, with proper incentives and training, move into RN positions and bolster the diversity of the profession. At the same time, a greater understanding of the reasons why racial and ethnic minorities are more likely to enter the workforce at the LPN/aide level than through educational programs leading to an RN could help elucidate mechanisms for recruiting and supporting these students in BSN, master's-level, and doctoral programs.

Associate's degree nursing programs and community colleges provide entry into the nursing profession for many nurses, but particularly for disadvantaged and underrepresented populations. Fulcher and Mullin (2011) note that “minority students in higher education are concentrated in community colleges” (p. 7), and studies have found that this holds true for both nursing and non-nursing students (American Association of Community Colleges, 2010; Bell, 2012; Mullin, 2012; Talamantes et al., 2014). African American and Hispanic/Latino graduates are more likely than their white counterparts to enter the nursing field with an associate's degree rather than a baccalaureate. Forty percent of new white RN graduates held a baccalaureate in 2013, compared with 36 percent of African American and 26 percent of Hispanic/Latino graduates (CCNA, n.d.-e). While white students may be more likely than minority students to enter the nursing profession with a baccalaureate degree, however, minority students may be slightly more likely to eventually hold a baccalaureate or higher degree. The 2008 National Sample Survey of RNs (HRSA, 2010) found that just under half (48.4 percent) of white non-Hispanic nurses held a baccalaureate or higher degree, compared with 52.5 percent of African Americans and 51.5 percent of Hispanics.

As these data indicate, both associate's degree programs and baccalaureate completion programs are important pathways for minority nurses. In addition, community college associate's degree programs make it easier for students with lower incomes to enter the profession. Because of the cost difference between community college and university programs, students attending community colleges to earn an associate's degree likely have lower incomes and different economic backgrounds relative to those attending entry-level baccalaureate programs (Fulcher and Mullin, 2011). Mullin (2012) highlights data (NCES, 2011) showing that community colleges enrolled 41 percent of all undergraduates living in poverty.

Community colleges, associate's degree programs, and baccalaureate completion programs all serve as pathways for minority and disadvantaged students to enter and succeed in nursing, and as the nursing profession moves toward the recommendation of The Future of Nursing for an 80 percent baccalaureate-trained workforce, these pathways—as well as the emerging models offering baccalaureate programs in community colleges—will remain important avenues to maintaining or increasing the diversity of the nursing workforce (see also Chapter 2). As noted by Jenny Landen, Leadership Council, New Mexico Nursing Education Consortium, at the committee's July 2015 workshop, “An important project goal [of the New Mexico Nursing Education Consortium] is to increase the diversity of the [baccalaureate]-prepared nursing workforce to better mirror our population. By placing the [baccalaureate] in the community colleges throughout the state with high minority populations, this opportunity will increase that diversity.”

Initiatives to retain diverse and underrepresented students in nursing education programs include financial support, mentorship, social and academic support, and professional counseling (Bleich et al., 2015; Bond et al., 2012; Brooks Carthon et al., 2014; Carter et al., 2015). These programs address diversity at all stages of education, from admission, to support during school, to the transition to the workforce. For example, the University of Illinois at Chicago College of Nursing recently adopted a holistic admissions process, which attempts to shape a diverse class by taking multiple attributes into account, looking at such standard criteria as grade point average and standardized test scores but also such attributes as race/ethnicity, leadership skills, and physical abilities (Scott and Zerwic, 2015; Weaver, 2015). For support during school, the Clinical Leadership Collaborative for Diversity in Nursing provides leadership development to racially, ethnically, and economically diverse nursing students at the University of Massachusetts at Boston. The program offers a scholarship and also uses mentoring to support the students participating in the program, which has seen a 100 percent graduation rate among participants (Banister et al., 2014). Finally, to help transition diverse students into the workforce, the Hausman Program at Massachusetts General Hospital offers a 6-week paid fellowship program for rising senior nursing students. Participants gain hands-on clinical experience in inpatient and ambulatory care settings and benefit from mentoring from minority staff nurses and educators. Deborah Washington, Director of Diversity for Patient Care Services, Massachusetts General Hospital, noted that “mentoring has become fundamental to a programmatic approach to the retention of nursing students as well as the working nurse.”12 She went on to say, “What is unique about [the Hausman Program] is that we help students understand the importance of their cultural identity in the practice environment, not only to their benefit, but to the benefit of ethnic minority patients. These students are taught to use their culture-based knowledge to increase patient engagement and to educate staff with cultural information in a peer support environment.”

FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS

Findings

This study yielded the following findings on diversity in the nursing profession:

Finding 4-1. Diversity continues to be a challenge in many health professions requiring postsecondary education, including nursing (see HRSA, 2015a).

Finding 4-2. Although the numbers and percentages of racial and ethnic minority nurses have generally increased in recent years, minority representation in the nursing workforce still is not representative of that in the general population. African American and Hispanic/Latino nurses in particular remain underrepresented in nursing.

Finding 4-3. There is significant variation from state to state in the diversity of both the nursing workforce and new nursing graduates compared with the diversity of the state population.

Finding 4-4. The Future of Nursing does not offer a stand-alone recommendation pertaining to diversity, but instead makes it a crosscutting issue in recommendations relating to education and leadership.

Finding 4-5. The Campaign established a Diversity Steering Committee and now requires all state Action Coalitions receiving funding through the Campaign's State Implementation Program or the RWJF-funded Academic Progression in Nursing program to develop diversity action plans.

Finding 4-6. As of May 2015, a total of 41 state Action Coalitions were working on developing or implementing diversity action plans, and 21 states had approved diversity action plans. Many state Action Coalitions are working on diversity issues even if this is not their main focus.

Finding 4-7. Most, but not all, states collect data on the racial/ethnic composition of their nursing workforce.

Finding 4-8. In addition to and outside of the work of the Campaign, many efforts have focused on increasing the diversity of the nursing workforce—especially programs designed to improve diversity in education—since the release of The Future of Nursing.

Conclusions

The committee drew the following conclusions about progress toward improving diversity in the nursing profession:

By making diversity one of its pillars, the Campaign has shone a spotlight on the issue of diversity in the nursing workforce. The requirement that states receiving funding through certain Campaign mechanisms (e.g., the State Implementation Program) focus on issues of diversity will help advance this issue at the state level. Further, work on diversity at the state level allows local coalitions to work toward creating a nursing workforce that is reflective of the diversity of the state's population.

Community colleges, associate's degree programs, and baccalaureate completion programs provide important pathways for diverse and disadvantaged students to enter the nursing profession; these educational pathways need to be maintained and strengthened.

The high proportions of underrepresented minorities among LPNs/LVNs and other health occupations requiring less education than RNs provides a potential pool of candidates for a more diverse nursing workforce.

RECOMMENDATION

Recommendation 6: Make Diversity in the Nursing Workforce a Priority. The Campaign should continue to emphasize recruitment and retention of a diverse nursing workforce as a major priority for both its national efforts and the state Action Coalitions. In broadening its coalition to include more diverse stakeholders (see Recommendation 1), the Campaign should work with others to assess progress and exchange information about strategies that are effective in increasing the diversity of the health workforce. To that end, the Campaign should take the following actions:

REFERENCES

- AACN (American Association of Colleges of Nursing). Enhancing diversity in the workforce. 2015. [September 24, 2015]. http://www

.aacn.nche .edu/media-relations /fact-sheets/enhancing-diversity. - Advisory Committee on Student Financial Assistance. Empty promises: The myth of college access in America. Washington, DC: Advisory Committee on Student Financial Assistance; 2002. [November 21, 2015]. http://files

.eric.ed .gov/fulltext/ED466814.pdf. - Advisory Committee on Student Financial Assistance. Access matters: Meeting the nation's college completion goals requires large increases in need-based grant aid. Washington, DC: Advisory Committee on Student Financial Assistance; 2013. [November 21, 2015]. http://files

.eric.ed .gov/fulltext/ED553377.pdf. - American Association of Community Colleges. Community colleges issues brief prepared for the 2010 White House Summit on Community Colleges. Washington, DC: American Association of Community Colleges; 2010. [September 18, 2015]. http://www

.aacc.nche .edu/AboutCC/whsummit /Documents/whsummit_briefs.pdf. - Banister G, Bowen-Brady HM, Winfrey ME. Using career mentors to support minority nursing students and facilitate their transition to practice. Journal of Professional Nursing. 2014;30(4):317–325. [PubMed: 25150417]

- Bell NE. Data sources: The role of community colleges on the pathway to graduate degree attainment. 2012. [September 18, 2015]. http://www

.cgsnet.org /data-sources-role-community-colleges-pathway-graduate-degree-attainment-0. - Bleich MR, MacWilliams BR, Schmidt BJ. Advancing diversity through inclusive excellence in nursing education. Journal of Professional Nursing. 2015;31(2):89–94. [PubMed: 25839947]

- Bond ML, Jones ME, Barr WJ, Carr GF, Williams SJ, Baxley S. Hardiness, perceived social support, perceived institutional support, and progression of minority students in a masters of nursing program. Hispanic Health Care International. 2012;10(3):109–117.

- Brooks Carthon JM, Nguyen T, Chittams J, Park E, Guevara J. Measuring success: Results from a national survey of recruitment and retention initiatives in the nursing workforce. Nursing Outlook. 2014;62(4):259–267. [PMC free article: PMC4550082] [PubMed: 24880900]

- Carter BM, Powell DL, Derouin AL, Cusatis J. Beginning with the end in mind: Cultivating minority nurse leaders. Journal of Professional Nursing. 2015;31(2):95–103. [PubMed: 25839948]

- CCNA (Center to Champion Nursing in America). Future of nursing: State Implementation Program 2012 request for proposals. Washington, DC: CCNA; 2011.

- CCNA. Future of nursing: State Implementation Program 2014 request for proposals. Washington, DC: CCNA; 2014.

- CCNA. Future of Nursing: Campaign for Action biannual operations report, August 1, 2014-May 31, 2015. Washington, DC: CCNA; 2015a. unpublished.

- CCNA. Future of Nursing: Campaign for Action dashboard indicators. 2015b. [September 12, 2015]. http:

//campaignforaction.org/dashboard. - CCNA. Campaign progress. n.d.-a. [September 24, 2015]. http:

//campaignforaction .org/campaign-progress. - CCNA. Campaign progress: Promoting diversity. n.d.-b. [September 24, 2015]. http:

//campaignforaction .org/campaignprogress /promoting-diversity. - CCNA. Directory of resources: Increasing diversity. n.d.-c. [September 24, 2015]. http:

//campaignforaction .org/directoryof-resources /increasing-diversity. - CCNA. Diversity steering committee. n.d.-d. [September 24. 2015]. http:

//campaignforaction .org/whos-involved /diversity-steering-committee. - CCNA. New RN graduates by degree type and race/ethnicity. n.d.-e. [November 5, 2015]. http:

//campaignforaction .org/campaign-progress /new-rn-graduates-degree-type-and-raceethnicity. - Donelan K, Romano C, DesRoches C, Applebaum S, Ward JR, Schoneboom BA, Hinshaw AS. National surveys of military personnel, nursing students, and the public: Drivers of military nursing careers. Military Medicine. 2014;179(5):565–572. [PubMed: 24806503]

- Fulcher R, Mullin CM. A data-driven examination of the impact of associate and bachelor's degree programs on the nation's nursing workforce. Washington, DC: American Association of Community Colleges; 2011. (AACC Policy Brief 2011-02PBL).

- HRSA (Health Resources and Services Administration). The rationale for diversity in the health professions: A review of the evidence. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2006.

- HRSA. The registered nurse population: Findings from the 2008 National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses. 2010. [November 5, 2015]. http://bhpr

.hrsa.gov /healthworkforce/rnsurveys /rnsurveyfinal.pdf. - HRSA. Health Resources and Services Administration fiscal year 2013 justification of estimates for Appropriations Committee. 2012. [September 18, 2015]. http://www

.hrsa.gov/about /budget/budgetjustification2013.pdf. - HRSA. Sex, race, and ethnic diversity of U.S. health occupations (2010-2012). Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, HRSA, National Center for Health Workforce Analysis; 2015a.

- HRSA. Health Resources and Services Administration fiscal year 2016 justification of estimates for Appropriations Committee. 2015b. [September 18, 2015]. http://www

.hrsa.gov/about /budget/budgetjustification2016.pdf. - IOM (Institute of Medicine). In the nation's compelling interest: Ensuring diversity in the health-care workforce. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed: 25009857]

- IOM. The future of nursing: Leading change, advancing health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed: 24983041]

- Landen J. The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health. Washington, DC: 2015. [July 27, 2015]. (Presentation to IOM Committee for Assessing Progress on Implementing the Recommendations of the Institute of Medicine Report).

- McMenamin P. Diversity among registered nurses: Slow but steady progress. 2015. [September 24, 2015]. http://www

.ananursespace .org/blogs/peter-mcmenamin /2015/08/21 /rn-diversity-note?ssopc=1. - More MS, Greer M. American women physicians in 2000: A history in progress. 2000. [September 24, 2015]. http://escholarship

.umassmed .edu/cgi/viewcontent .cgi?article =1050&context=lib_articles. - Mullin CM. Why access matters: The community college student body. Washington, DC: American Association of Community Colleges; 2012. [September 18, 2015]. (AACC Policy Brief 2012-01PBL). http://www

.aacc.nche .edu/Publications/Briefs /Documents/PB_AccessMatters.pdf. - NCES (National Center for Education Statistics). 2007-2008 National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS: 08) [Data file]. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, Institute for Education Sciences; 2011.

- NCSL (National Conference of State Legislatures). Workforce diversity. 2014. [September 24, 2015]. http://www

.ncsl.org/documents /health/workforcediversity814 .pdf. - OMH (Office of Minority Health). Reflecting America's population: Diversifying a competent health care workforce for the 21st century. 2011. [September 24, 2015]. http:

//minorityhealth .hhs.gov/Assets/pdf /Checked/1/FinalACMHWorkforceReport.pdf. - Scott LD, Zerwic J. Holistic review in admissions: A strategy to diversify the nursing workforce. Nursing Outlook. 2015;63(4):488–495. [PubMed: 26187088]

- The Sullivan Alliance. Initiatives. 2015. [September 24, 2015]. http://www

.thesullivanalliance .org/cue/initiatives.html. - Sullivan Commission on Diversity in the Healthcare Workforce. Missing persons: Minorities in the health professions. Washington, DC: The Sullivan Commission; 2004.

- Talamantes E, Mangione CM, Gonzalez K, Jimenez A, Gonzalez F, Moreno G. Community college pathways: Improving the U.S. physician workforce pipeline. Academic Medicine. 2014;89(12):1649–1656. [PMC free article: PMC4245373] [PubMed: 25076199]

- TCC Group. Future of Nursing: Campaign for Action: Action Coalition Survey. Philadelphia, PA: TCC Group; 2013. unpublished.

- U.S. Army. Army nursing career: Army nurse requirements & info. n.d. [September 24, 2015]. http://www

.goarmy.com/amedd/nurse.html. - U.S. Census Bureau. Men in nursing occupations: American Community Survey highlight report. 2013. [September 24, 2015]. http://www

.census.gov /people/io/files/Men _in_Nursing_Occupations.pdf. - VA (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs). Realizing the future of nursing: VA nurses tell their story. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration; 2015a.

- VA. National nursing awards: Nursing innovation awards. 2015b. [September 24, 2015]. http://www

.va.gov/NURSING /About/nationalawards.asp. - Villarruel A, Washington D, Lecher WT, Carver NA. A more diverse nursing workforce: Greater diversity is good for the country's health. American Journal of Nursing. 2015;115(5):57–62. [PubMed: 25906230]

- Weaver T. The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health. Washington, DC: 2015. [July 27, 2015]. (Presentation to IOM Committee for Assessing Progress on Implementing the Recommendations of the Institute of Medicine Report).

Footnotes

- 1

Where possible, this chapter uses the racial and ethnic classifications (e.g., “Hispanic or Latino”) used in the original data source.

- 2

Personal communications, C. Romano, Uniformed Services University, September 2, 2015, and September 13, 2015.

- 3

Ibid.

- 4

Personal communication, S. Hassmiller, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, September 19, 2015.

- 5

Derived from 2011-2013 American Community Survey data.

- 6

Ibid.

- 7

Data received from the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN), August 28, 2015.

- 8

Data received from AACN, August 28, 2015.

- 9

Derived from 2011-2013 ACS data.

- 10

Ibid.

- 11

Data received from AACN, August 28, 2015.

- 12

Personal communication, D. Washington, Massachusetts General Hospital, August 12, 2015.

- Promoting Diversity - Assessing Progress on the Institute of Medicine Report The...Promoting Diversity - Assessing Progress on the Institute of Medicine Report The Future of Nursing

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

See more...