NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012-.

LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet].

Show detailsOVERVIEW

Introduction

Meprobamate is a sedative used for anxiety and insomnia first made available in the 1950s when it became very popular, but which is now rarely used. Meprobamate therapy was not associated with liver enzyme elevations and has not been linked to instances of clinically apparent liver injury.

Background

Meprobamate (me" proe bam' ate) is a bis-carbamate ester which was found to have antianxiety activity and was introduced into medical use in the 1950s. Meprobamate rapidly became one of the most widely used psychotropic agents, being considered a “tranquillizer”. Commonly known by its brand name Miltown, it was approved for use in anxiety, but was widely used as a sedative and for insomnia. The sedative effects of meprobamate resemble those of the benzodiazepines, and it is known to bind to the GABA-A receptor. However, the precise mechanism of action of meprobamate is unclear. Meprobamate also has major abuse potential and many cases of dependency, habituation and overdose have been described. Withdrawal can lead to hallucinations and seizures. Meprobamate was approved for use in generalized anxiety disorders in the United States in 1955, but it is currently rarely used and is classified as a Schedule IV controlled substance because of its potential for abuse and dependency. Nevertheless, meprobamate remains available in several generic forms as 200 and 400 mg tablets. In addition, the muscle relaxant carisoprodol is a prodrug of meprobamate and is clinically available, although now it is also classified as a Schedule IV controlled substance [January 2012]. The recommended dosage of meprobamate is 1200 to 1600 mg daily in three or four divided doses. Side effects may include diarrhea, nausea, flatulence, drowsiness, ataxia, dizziness, headache, weakness, nervousness, euphoria, overstimulation and physical dependence. Uncommon but potentially severe adverse reactions include hypersensivity reactions including Stevens Johnson syndrome, embryo-fetal toxicity, addiction and dependence, stupor, coma and death from overdose.

Hepatotoxicity

Rates of serum enzyme elevations during meprobamate therapy have not been reported. While instances of clinically apparent liver injury due to meprobamate have been mentioned in review articles, no cases with specific information on clinical features have appeared in the published literature. Thus, meprobamate may be capable of causing clinically apparent liver injury, but it must be rare. Meprobamate is metabolized in the liver via the cytochrome P450 system and has major potential for drug-drug interactions. Meprobamate can exacerbate symptoms of porphyria. Serious allergic reactions to meprobamate have been reported including Stevens Johnson syndrome. In cases of meprobamate overdose, the cause of death has been respiratory suppression and not liver failure, although liver histology was not well defined.

Likelihood score: E* (unproven but suspected cause of liver injury).

Drug Class: Sedatives and Hypnotics, Miscellaneous

PRODUCT INFORMATION

REPRESENTATIVE TRADE NAMES

Meprobamate – Generic

DRUG CLASS

Sedatives and Hypnotics

Product labeling at DailyMed, National Library of Medicine, NIH

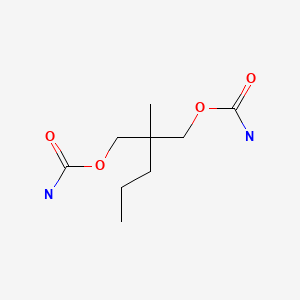

CHEMICAL FORMULA AND STRUCTURE

| DRUG | CAS REGISTRY NUMBER | MOLECULAR FORMULA | STRUCTURE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Meprobamate | 57-53-4 | C9-H18-N2-O4 |

|

ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY

References updated: 21 January 2020

- Zimmerman HJ. Psychotropic and anticonvulsant agents. In, Zimmerman HJ. Hepatotoxicity: the adverse effects of drugs and other chemicals on the liver. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1999, pp. 483-516.(Expert review of hepatotoxicity published in 1999; mentions that there have been three reported instances of liver injury attributed to meprobamate, but clinical features are not specifically discussed).

- Kanel GC. Histopathology of drug-induced liver disease. In, Kaplowitz N, DeLeve LD, eds. Drug-induced liver disease. 2nd ed. New York: Informa Healthcare USA, 2007, p. 284.(Meprobamate is listed as causing cholestasis with inflammation, but is not specifically discussed).

- Mihic SJ, Mayfield J, Harris RA. Hypnotics and sedatives. In, Brunton LL, Chabner BA Hillal-Dandan R, Knollman BC, eds. Goodman & Gilman's the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 13th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2018, pp. 339-54.(Textbook of pharmacology and therapeutics).

- Selling LS. Clinical study of a new tranquilizing drug; use of miltown(2-methyl-2-n-propyl-1,3-propanediol dicarbamate). J Am Med Assoc. 1955;157:1594–6. [PubMed: 14367012](Among 187 patients with anxiety treated with meprobamate in a private practice, 64 recovered, 88 were improved, 35 were not improved and 3 patients developed allergic reactions; states that meprobamate "is not habit forming", but does not mention liver complications).

- Friedman HT, Marmelzat WL. Adverse reactions to meprobamate. J Am Med Assoc. 1956;162:628–30. [PubMed: 13366645](Description of 7 cases of severe adverse events due to meprobamate, including rash [n=5], ocular palsy and severe diarrhea; no mention of liver injury).

- Ewing JA, Fullilove RE. Addiction to meprobamate. N Engl J Med. 1957;257:76–7. [PubMed: 13452049](32 year old man taking 4 to 8 g of meprobamate daily developed headaches, muscle twitching, anxiety and somatic complaints during withdrawal).

- Haizlip TM, Ewing JA. Meprobamate habituation: a controlled clinical study. N Engl J Med. 1958;258:1181–6. [PubMed: 13552940](75 residents of a State mental hospital were given meprobamate [3.2 and 6.4 g daily] or placebo for 40 days and then "surreptitiously" switched to placebo; withdrawal symptoms included insomnia, anxiety, tremors, nausea, hallucinations, acute psychosis and convulsions; no hepatic complications mentioned).

- Cowger ML, Labbe RF. Contraindications of biological-oxidation inhibitors in the treatment of porphyria. Lancet. 1965;1(7376):88–9. [PubMed: 14234213](Mentions that clinical relapses of acute intermittent porphyria have occurred with drugs other than barbiturates, including chlordiazepoxide and meprobamate).

- Ayd FJ Jr. Meprobamate: A decade of experience. Psychosomatics. 1964;5:82–7. [PubMed: 14130886](Review of the safety and efficacy of meprobamate after a decade of its wide scale clinical use; states "that meprobamate is free from hepatotoxicity is incontrovertible").

- Maddock RK Jr, Bloomer HA. Meprobamate overdosage. Evaluation of its severity and methods of treatment. JAMA. 1967;201:999–1003. [PubMed: 6072491](10 patients with meprobamate overdose [1.6 to 30 g], ages 16 to 48 years, 7 women, 8 in coma, 1 died; plasma levels correlated with coma state and there was rapid renal clearance; no mention of liver injury).

- Schwartz HS. Acute meprobamate poisoning with gastrotomy and removal of a drug-containing mass. N Engl J Med. 1976;295:1177–8. [PubMed: 980021](56 year old woman developed coma and respiratory failure after overdose of 36 g of meprobamate, with persistent high levels in serum, gastroscopy demonstrating a mass of undigested meprobamate tablets in the stomach, ultimately requiring surgical removal; no mention of liver injury).

- Crome P, Higgenbottom T, Elliott JA. Severe meprobamate poisoning: successful treatment with haemoperfusion. Postgrad Med J. 1977;53:698–9. [PMC free article: PMC2496842] [PubMed: 593997](56 year old woman with meprobamate overdose developed coma and respiratory depression, improved by hemoperfusion with charcoal column; no mention of liver injury).

- Kintz P, Tracqui A, Mangin P, Lugnier AA. Fatal meprobamate self-poisoning. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1988;9:139–40. [PubMed: 3381792](35 year old man found dead with lethal levels of meprobamate in blood; no description of liver histology).

- Littrell RA, Sage T, Miller W. Meprobamate dependence secondary to carisoprodol (Soma) use. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1993;19:133–4. [PubMed: 8438828](37 year old woman was found to have meprobamate on urine screening after a motor vehicle accident, but denied taking meprobamate, but did admit to use of carisoprodol which she was later found to regularly abuse).

- Bailey DN, Briggs JR. Carisoprodol: an unrecognized drug of abuse. Am J Clin Pathol. 2002;117:396–400. [PubMed: 11888078](Over a 6 month period, 19 patients were found to have carisoprodol in urine on comprehensive drug screens, 12 with decrease in level of consciousness; liver injury not mentioned).

- Buire AC, Vitry F, Hoizey G, Lamiable D, Trenque T. Overdose of meprobamate: plasma concentration and Glasgow Coma Scale. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;68:126–7. [PMC free article: PMC2732949] [PubMed: 19660012](Among 59 cases of meprobamate overdose, plasma levels correlated roughly with degree of coma; only one patient died).

- Chalasani N, Fontana RJ, Bonkovsky HL, Watkins PB, Davern T, Serrano J, Yang H, Rochon J., Drug Induced Liver Injury Network (DILIN). Causes, clinical features, and outcomes from a prospective study of drug-induced liver injury in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1924–34. [PMC free article: PMC3654244] [PubMed: 18955056](Among 300 cases of drug induced liver disease in the US collected from 2004 to 2008, none were attributed to meprobamate).

- Fathallah N, Zamy M, Slim R, Fain O, Hmouda H, Bouraoui K, Ben Salem C, Biour M. Acute pancreatitis in the course of meprobamate poisoning. JOP. 2011;12:404–6. [PubMed: 21737904](43 year old woman took an overdose of meprobamate [60 g] and was admitted in stupor and found to have pancreatitis [bilirubin 1.0 mg/dL, ALT 65 U/L, Alk P 115 U/L, lipase 21.3 times ULN], resolving with temporary ventilator support and hydration).

- Herzberg D. Blockbusters and controlled substances: Miltown, Quaalude, and consumer demand for drugs in postwar America. Stud Hist Philos Biol Biomed Sci. 2011;42:415–26. [PubMed: 22035715](History of discovery, approval, marketing and subsequent wide scale use and abuse of meprobamate).

- Reeves RR, Burke RS, Kose S. Carisoprodol: update on abuse potential and legal status. South Med J. 2012;105:619–23. [PubMed: 23128807](Review of the clinical features and frequency of carisoprodol abuse which increased between 2001 and 2008 and decreased with the introduction of restrictions on its sale; carisoprodol was classified as a schedule IV controlled substance in the US starting in January 2012).

- Hernández N, Bessone F, Sánchez A, di Pace M, Brahm J, Zapata R, A, Chirino R, et al. Profile of idiosyncratic drug induced liver injury in Latin America: an analysis of published reports. Ann Hepatol. 2014;13:231–9. [PubMed: 24552865](Among 176 reports of drug induced liver injury from Latin America published between 1996 and 2012, none were attributed to meprobamate).

- Chalasani N, Bonkovsky HL, Fontana R, Lee W, Stolz A, Talwalkar J, Reddy KR, et al. United States Drug Induced Liver Injury Network. Features and outcomes of 899 patients with drug-induced liver injury: The DILIN Prospective Study. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:1340–52.e7. [PMC free article: PMC4446235] [PubMed: 25754159](Among 899 cases of drug induced liver injury enrolled in a US prospective study between 2004 and 2013, none were attributed to sedatives, meprobamate or carisoprodol).

- PMCPubMed Central citations

- PubChem SubstanceRelated PubChem Substances

- PubMedLinks to PubMed

- OBSERVATIONS ON THE ANTIHYPERTENSIVE AND SEDATIVE EFFECTS OF MEBUTAMATE, MEPROBAMATE AND RESERPINE.[Can Med Assoc J. 1963]OBSERVATIONS ON THE ANTIHYPERTENSIVE AND SEDATIVE EFFECTS OF MEBUTAMATE, MEPROBAMATE AND RESERPINE.MORIN Y, TURMEL L, GRANTHAM H, FORTIER J. Can Med Assoc J. 1963 Nov 9; 89(19):980-2.

- [MEPROBAMATE IN OBSTETRICS].[Dia Med. 1963][MEPROBAMATE IN OBSTETRICS].BALLAS R. Dia Med. 1963 Sep 2; 35:1370-1.

- [ANXIETY AND INSOMNIA. APROPOS OF A NEW MEDICAMENTOUS COMBINATION: LE FH 040-3].[Lyon Med. 1964][ANXIETY AND INSOMNIA. APROPOS OF A NEW MEDICAMENTOUS COMBINATION: LE FH 040-3].PONT M, CHAPUY A, VEDRINNE J. Lyon Med. 1964 Feb 23; 211:465-9.

- Review Hops.[LiverTox: Clinical and Researc...]Review Hops.. LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury. 2012

- Review Passionflower.[LiverTox: Clinical and Researc...]Review Passionflower.. LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury. 2012

- Meprobamate - LiverToxMeprobamate - LiverTox

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

See more...