NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012-.

LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet].

Show detailsOVERVIEW

Introduction

Lonafarnib is an oral, small molecule inhibitor of farnesyltransferase that is used to treat Hutchison-Gilford progeria syndrome and is under investigation as therapy of chronic hepatitis D. Lonafarnib is associated with transient and usually mild elevations in serum aminotransferase levels during therapy, but has not been linked to cases of clinically apparent acute liver injury.

Background

Lonafarnib (loe” na far’ nib) is an orally available, specific inhibitor of farnesyltransferase and is approved for the treatment of Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS), a rare autosomal dominant form of accelerated aging (arising in 1 in 4 million live births). Persons with HGPS develop cardiovascular disease at a young age and typically die of myocardial infarction, heart failure or stroke before the age of 20. Other manifestations of HGPS include sclerotic skin, joint contracture, bone abnormalities, alopecia, and growth impairment. Lonafarnib acts by prevention of farnesylation of proteins, a post-translational modification which alters membrane attachment. In HGPS a point mutation in the LMNA gene results in an abnormal lamin A protein called “progerin”. Lamin A is a normal component of the nuclear envelope providing structural organization to the nucleus and supporting normal chromatic function, DNA replication, RNA transcription, cell cycling and apoptosis. The abnormal progerin protein, however, lacks the ability to remove the post-translational isoprenyl that allows for membrane attachment. As a result, the abnormal lamin A remains and accumulates, acting as a dominant negative in causing abnormal nuclear membranes. The clinical manifestations of HGPS appear to be due to the abnormalities of nuclear membranes. In animal models and in subsequent human clinical trials, lonafarnib therapy was associated with a decrease in progerin farnesylation as well as a decrease in its accumulation, in clinical abnormalities and cardiovascular complications, resulting in prolonged survival. Lonafarnib was approved for use in HGPS in the United States in 2020. Lonafarnib has also been evaluated in several forms of cancer associated with abnormal RAS (whose activation is dependent on farnesyltransferase) and for chronic hepatitis D virus infection (the HDV replicative cycle requires the same enzyme). Current indications for lonafarnib are limited to patients with HGPS (or other processing-deficient progeroid laminopathies) who are 12 months of age or above with body surface area of at least 0.39/m2. Lonafarnib is available in capsules of 50 and 75 mg under the brand name Zokinvy. The recommended initial dose is 115 mg/m2 twice daily increasing after 4 months to 150 mg/m2 twice daily. Side effects are common, particularly with higher doses and include diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, musculoskeletal pain, fatigue, electrolyte abnormalities (hypokalemia, hyponatremia, hypocalcemia), cough, hypertension, myelosuppression and infections. Severe adverse events include dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, nephrotoxicity, retinal abnormalities, impaired fertility, and embryo-fetal toxicity. Monitoring of electrolytes, complete blood counts and liver enzymes is recommended.

Hepatotoxicity

In the small prelicensure clinical trials conducted in children with progeria, serum aminotransferase elevations occurred in 35% of lonafarnib treated subjects but were usually mild and self-limited, rising to above 3 times the upper limit of normal (ULN) in only 5%. There were no liver related serious adverse events and no patient had a concurrent elevation in serum aminotransferase and bilirubin levels. Since approval of lonafarnib, there have been no published reports of drug induced liver injury associated with its use, although clinical experience with the drug, particularly with long term therapy, has been limited.

Likelihood score: E* (unproven but suspected rare cause of clinically apparent liver injury).

Mechanism of Injury

The causes of serum enzyme elevations during lonafarnib therapy are not known. Lonafarnib is metabolized in the liver largely through the cytochrome P450 pathway and specifically by CYP 3A4, and liver injury may be related to production of a toxic or immunogenic intermediate. Because it is a substrate for CYP 3A4, lonafarnib is susceptible to drug-drug interactions with agents that inhibit or induce this specific hepatic microsomal activity.

Outcome and Management

Monitoring of laboratory tests including routine liver tests is recommended for patients treated with lonafarnib. Serum aminotransferase elevations above 5 times the upper limit of normal (if confirmed) or any elevations accompanied by jaundice or symptoms should lead to dose reduction or temporary cessation. There are no data to suggest a cross reactivity in risk for hepatic injury between lonafarnib and other small molecule enzyme inhibitors.

Drug Class: Genetic Disease Agents, Protein Kinase Inhibitors

PRODUCT INFORMATION

REPRESENTATIVE TRADE NAMES

Lonafarnib – Zokinvy®

DRUG CLASS

Genetic Disease Agents, Small Molecule Enzyme Inhibitors

Product labeling at DailyMed, National Library of Medicine, NIH

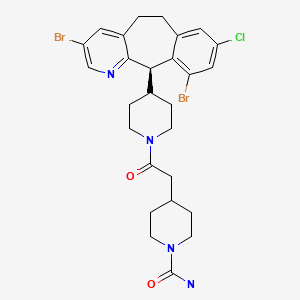

CHEMICAL FORMULA AND STRUCTURE

| DRUG | CAS REGISTRY NO. | MOLECULAR FORMULA | STRUCTURE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lonafarnib | 193275-84-2 | C27-H31-Br2-Cl-N4-O2 |

|

ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY

References updated: January 7, 2020

Abbreviations: HGPS, Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome.

- Zimmerman HJ. Zimmerman HJ. Hepatotoxicity: the adverse effects of drugs and other chemicals on the liver. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1999.(Review of hepatotoxicity published in 1999 before the availability of protein kinase inhibitors such as lonafarnib).

- DeLeve LD. Erlotinib. Cancer chemotherapy. In, Kaplowitz N, DeLeve LD, eds. Drug-induced liver disease. 3rd ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2013, pp. 556.(Review of hepatotoxicity of cancer chemotherapeutic agents discusses several small molecular weight enzyme inhibitors including imatinib, gefitinib, erlotinib and crizotinib, but not lonafarnib).

- Wellstein A, Giaccone G, Atkins MB, Sausville EA. Pathway-targeted therapies: monoclonal antibodies, protein kinase inhibitors, and various small molecules. In, Brunton LL, Hilal-Dandan R, Knollman BC, eds. Goodman & Gilman's the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 13th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2018, pp. 1203-36.(Textbook of pharmacology and therapeutics; lonafarnib is not discussed specifically).

- FDA. https://www

.accessdata .fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs /nda/2020/213969Orig1s000IntegratedR.pdf. (FDA website with medical review of efficacy and safety of lonafarnib, which formed the basis of its approval for use in Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome [HGPS], mentions that in registration trials in children there were no liver related serious adverse events, and although ALT elevations arose in 35% of children, none were associated with symptoms or jaundice). - Merideth MA, Gordon LB, Clauss S, Sachdev V, Smith AC, Perry MB, Brewer CC, et al. Phenotype and course of Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:592–604. [PMC free article: PMC2940940] [PubMed: 18256394](Detailed description of clinical features in 15 children with HGPS characterized by decrease in cardiovascular function with age, sclerotic skin, joint contractures, bone abnormalities including osteoporosis, hearing loss, eye abnormalities, alopecia, and growth impairment; ALT levels were normal in all except two children with mild elevations).

- Feldman EJ, Cortes J, DeAngelo DJ, Holyoake T, Simonsson B, O'Brien SG, Reiffers J, et al. On the use of lonafarnib in myelodysplastic syndrome and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2008;22:1707–11. [PubMed: 18548095](Among 67 adults with myelodysplastic syndrome or chronic myelomonocytic leukemia treated with lonafarnib [200 or 300 mg twice daily], responses occurred in 24% and 2 patients had a complete remission, while gastrointestinal adverse events were common including diarrhea [79%] which led to discontinuation in 19%; no mention of ALT elevations or hepatotoxicity).

- Ravoet C, Mineur P, Robin V, Debusscher L, Bosly A, André M, El Housni H, et al. Farnesyl transferase inhibitor (lonafarnib) in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome or secondary acute myeloid leukaemia: a phase II study. Ann Hematol. 2008;87:881–5. [PubMed: 18641985](Among 15 patients with myelodysplastic syndrome or secondary acute leukemia treated with lonafarnib [200 mg twice daily in 4-week courses], response rates were minimal [7%, 1 patient] and adverse events were common and often dose limiting; 4 patients [26%] had ALT elevations but all were self-limited, and there were no severe hepatic adverse events).

- Hanrahan EO, Kies MS, Glisson BS, Khuri FR, Feng L, Tran HT, Ginsberg LE, et al. A phase II study of lonafarnib (SCH66336) in patients with chemorefractory, advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Am J Clin Oncol. 2009;32:274–9. [PubMed: 19433965](Among 15 patients with refractory head and neck cancer treated with lonafarnib [200 mg twice daily in 28 day cycles], no objective responses were observed and adverse events were common including diarrhea [71%], nausea [64%] and fatigue [57%]; no mention of ALT elevations or hepatotoxicity).

- Gordon LB, Kleinman ME, Miller DT, Neuberg DS, Giobbie-Hurder A, Gerhard-Herman M, Smoot LB, et al. Clinical trial of a farnesyltransferase inhibitor in children with Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:16666–71. [PMC free article: PMC3478615] [PubMed: 23012407](Among 25 children with HGPS treated with lonafarnib [115 mg/m2 escalated to 150 mg/m2] for at least 2 years, weight and cardiovascular endpoints improved overall and while adverse events were frequent, none resulted in drug discontinuations including diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, fatigue and ALT elevations in 10 patients [40%] which were above 3 times ULN in only 2 [8%] and were asymptomatic, anicteric, usually transient, and mostly arising during the first 4 months of therapy).

- Gordon LB, Massaro J, D'Agostino RB Sr, Campbell SE, Brazier J, Brown WT, Kleinman ME, et al. Progeria Clinical Trials Collaborative. Impact of farnesylation inhibitors on survival in Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Circulation. 2014;130:27–34. [PMC free article: PMC4082404] [PubMed: 24795390](Analysis of survival in 43 patients with HGPS treated with lonafarnib vs matched controls selected from an untreated cohort of 161 children [median survival of 14.6 years] demonstrated improved survival with lonafarnib treatment, survival extension averaging 1.6 years during the median follow up of 5.3 years).

- Koh C, Canini L, Dahari H, Zhao X, Uprichard SL, Haynes-Williams V, Winters MA, et al. Oral prenylation inhibition with lonafarnib in chronic hepatitis D infection: a proof-of-concept randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2A trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:1167–74. [PMC free article: PMC4700535] [PubMed: 26189433](Among 14 patients with chronic hepatitis D treated with lonafarnib [100 or 200 mg] or placebo once daily for 28 days, there was a decline in HDV RNA in treated subjects [-0.7 and -1.5 log] but not with placebo, and adverse events were common with the higher dose but did not lead to early discontinuation; serum ALT levels were elevated in all three groups before treatment and did not change significantly after starting therapy).

- Gordon LB, Kleinman ME, Massaro J, D'Agostino RB Sr, Shappell H, Gerhard-Herman M, Smoot LB, et al. Clinical trial of the protein farnesylation inhibitors lonafarnib, pravastatin, and zoledronic acid in children with Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Circulation. 2016;134:114–25. [PMC free article: PMC4943677] [PubMed: 27400896](Among 37 patients with HGPS treated with the combination of lonafarnib with pravastatin and zoledronic acid [agents that inhibit farnesylation], bone mineral density improved but there was little evidence that the combination was superior to lonafarnib alone in reducing cardiovascular complications; ALT elevations arose in 11 subjects [30%] and were above 5 times ULN in 4 [11%]).

- Gordon LB, Shappell H, Massaro J, D'Agostino RB Sr, Brazier J, Campbell SE, Kleinman ME, et al. Association of lonafarnib treatment vs no treatment with mortality rate in patients with Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. JAMA. 2018;319:1687–95. [PMC free article: PMC5933395] [PubMed: 29710166](Analysis of survival among 63 patients with HGPS treated with lonafarnib compared to 63 matched untreated historical control patients [from a progeria registry] found a lower mortality rate with lonafarnib therapy with 4 deaths [6%] compared to 17 [27%] in untreated controls followed for a similar period of time).

- Gilman C, Heller T, Koh C. Chronic hepatitis delta: A state-of-the-art review and new therapies. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:4580–97. [PMC free article: PMC6718034] [PubMed: 31528088](Review of the epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical course and therapy of chronic hepatitis D mentions that lonafarnib has been shown to lower serum levels of HDV RNA and prolonged therapy to be associated with improvements in serum aminotransferase levels, although with difficult side effects when used in high doses and in combination with alpha interferon).

- PMCPubMed Central citations

- PubChem SubstanceRelated PubChem Substances

- PubMedLinks to PubMed

- Lonafarnib improves cardiovascular function and survival in a mouse model of Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome.[Elife. 2023]Lonafarnib improves cardiovascular function and survival in a mouse model of Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome.Murtada SI, Mikush N, Wang M, Ren P, Kawamura Y, Ramachandra AB, Li DS, Braddock DT, Tellides G, Gordon LB, et al. Elife. 2023 Mar 17; 12. Epub 2023 Mar 17.

- Review Lonafarnib: First Approval.[Drugs. 2021]Review Lonafarnib: First Approval.Dhillon S. Drugs. 2021 Feb; 81(2):283-289.

- Baricitinib, a JAK-STAT Inhibitor, Reduces the Cellular Toxicity of the Farnesyltransferase Inhibitor Lonafarnib in Progeria Cells.[Int J Mol Sci. 2021]Baricitinib, a JAK-STAT Inhibitor, Reduces the Cellular Toxicity of the Farnesyltransferase Inhibitor Lonafarnib in Progeria Cells.Arnold R, Vehns E, Randl H, Djabali K. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Jul 12; 22(14). Epub 2021 Jul 12.

- Clinical Trial of the Protein Farnesylation Inhibitors Lonafarnib, Pravastatin, and Zoledronic Acid in Children With Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome.[Circulation. 2016]Clinical Trial of the Protein Farnesylation Inhibitors Lonafarnib, Pravastatin, and Zoledronic Acid in Children With Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome.Gordon LB, Kleinman ME, Massaro J, D'Agostino RB Sr, Shappell H, Gerhard-Herman M, Smoot LB, Gordon CM, Cleveland RH, Nazarian A, et al. Circulation. 2016 Jul 12; 134(2):114-25.

- Review Lonafarnib for cancer and progeria.[Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2012]Review Lonafarnib for cancer and progeria.Wong NS, Morse MA. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2012 Jul; 21(7):1043-55. Epub 2012 May 24.

- Lonafarnib - LiverToxLonafarnib - LiverTox

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

See more...